The Art of Building – with a Floatingly Light Touch: In Conversation with Frei Otto (2000)

DETAIL 06/2000

In 2000, Frei Otto was the talk of the town, with the Japanese paper tube pavilion he developed alongside Shigeru Ban for the Hanover World Expo being one of the event’s most-acclaimed structures. Three years previously he had bestowed Stuttgart, his long-time home city, with the design for a new, underground main railway station devised in collaboration with Christoph Ingenhoven’s studio. And in Munich conversion of Otto’s main work – the 1972 Olympic Stadium – into one solely dedicated to football was the subject of much debate.

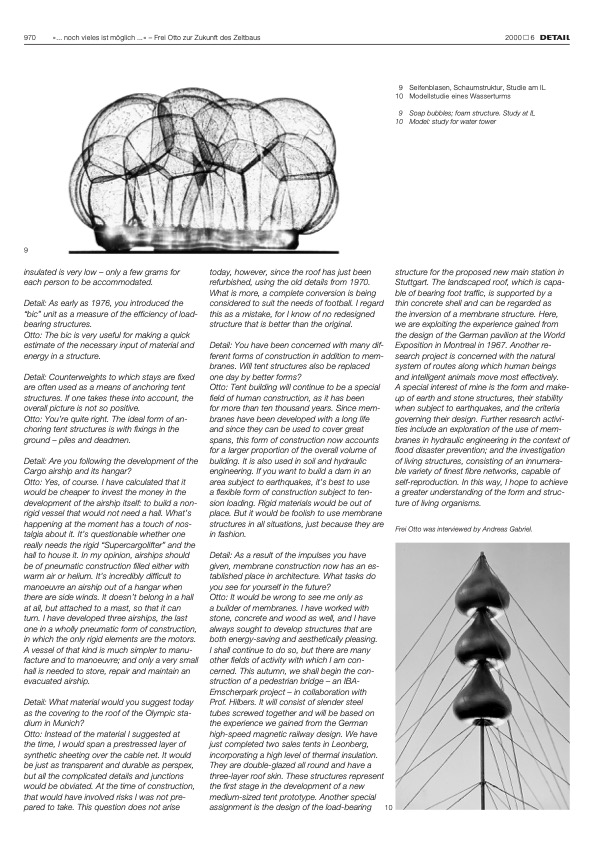

Enough topics, in other words, for the interview that Andreas Gabriel conducted with the architect and later Pritzker laureate for the June 2000 issue of Detail. The focus was naturally placed on membrane structures, the subject of the architect’s dissertation “Das hängende Dach“ (The Suspended Roof) in 1954. The inspiration for this came from America, to be exact from the Raleigh Arena in North Carolina, designed by Matthew Nowicki and completed in 1953, with Frei Otto getting to know its design on a study tour.

However, there’s more to membrane structures than meets the eye since a lot of experience in the field is required if they are to also convince aesthetically. As Frei Otto criticised in the interview: “The reason there is so little building art in tent construction today is because too little technical and design work is undertaken. A very superficial approach is adopted at various points, and too much reliance is placed in existing solutions.”

Maybe this is because the form-finding processes involved in designing membrane structures do not come naturally to many architects. As Frei Otto said: “Architects wish to design their own forms; but if the automatic form-finding process that occurs in membrane construction is not respected, the result is unlikely to be very good.”

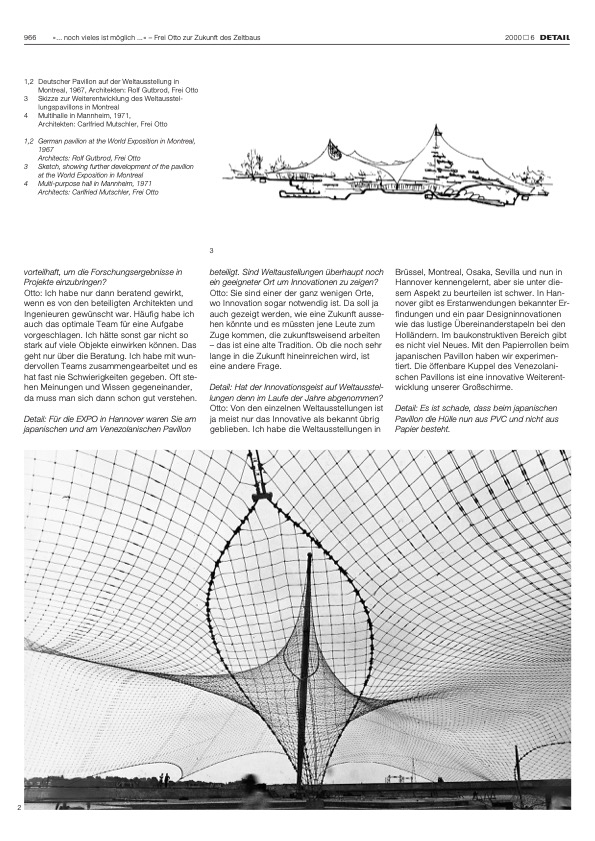

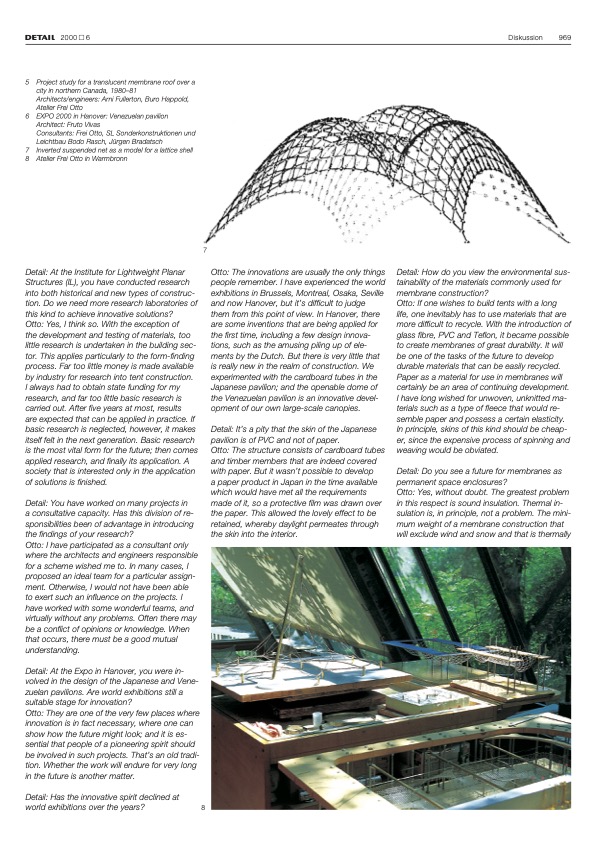

For the Expo 2000 in Hanover, Frei Otto and his studio contributed to the design not only of the Japanese but also the Venezuelan pavilion. Asked whether world expositions are really the right place for innovation, he answered: “They are one of the very few places where innovation is in fact necessary, where one can show how the future might look; and it is essential that people of a pioneering spirit should be involved in such projects. That’s an old tradition. Whether the work will endure for very long in the future is another matter.“

Of interest is also the question which material Frei Otto would suggest today for the tent roof of Munich’s Olympic Stadium if he had to construct it again: “I would span a prestressed layer of synthetic sheeting over the cable net. It would be just as transparent and durable as perspex, but all the complicated details and junctions would be obviated. At the time of construction, that would have involved risks I was not prepared to take.“