From prison to hotel

Hotel Wilmina in Berlin

© Patricia Parinejad

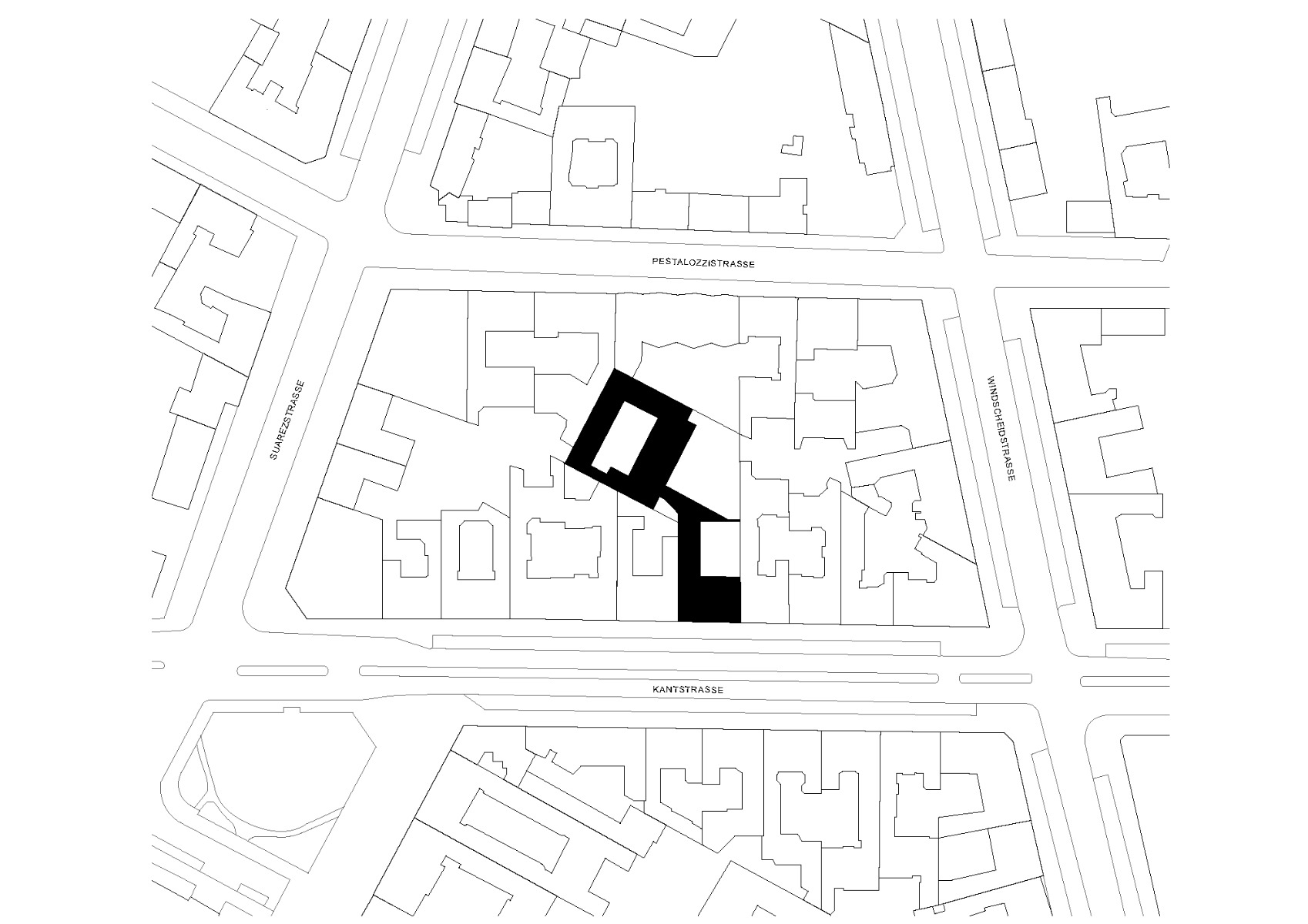

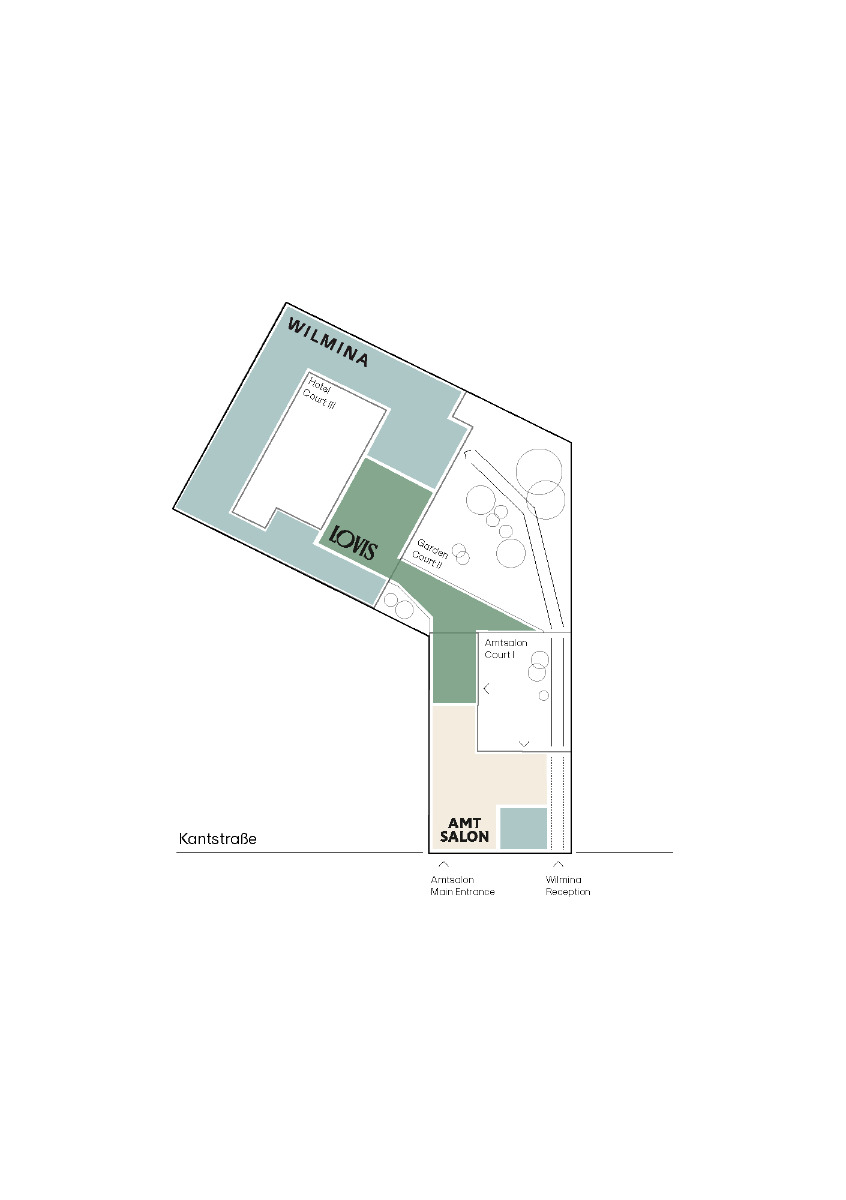

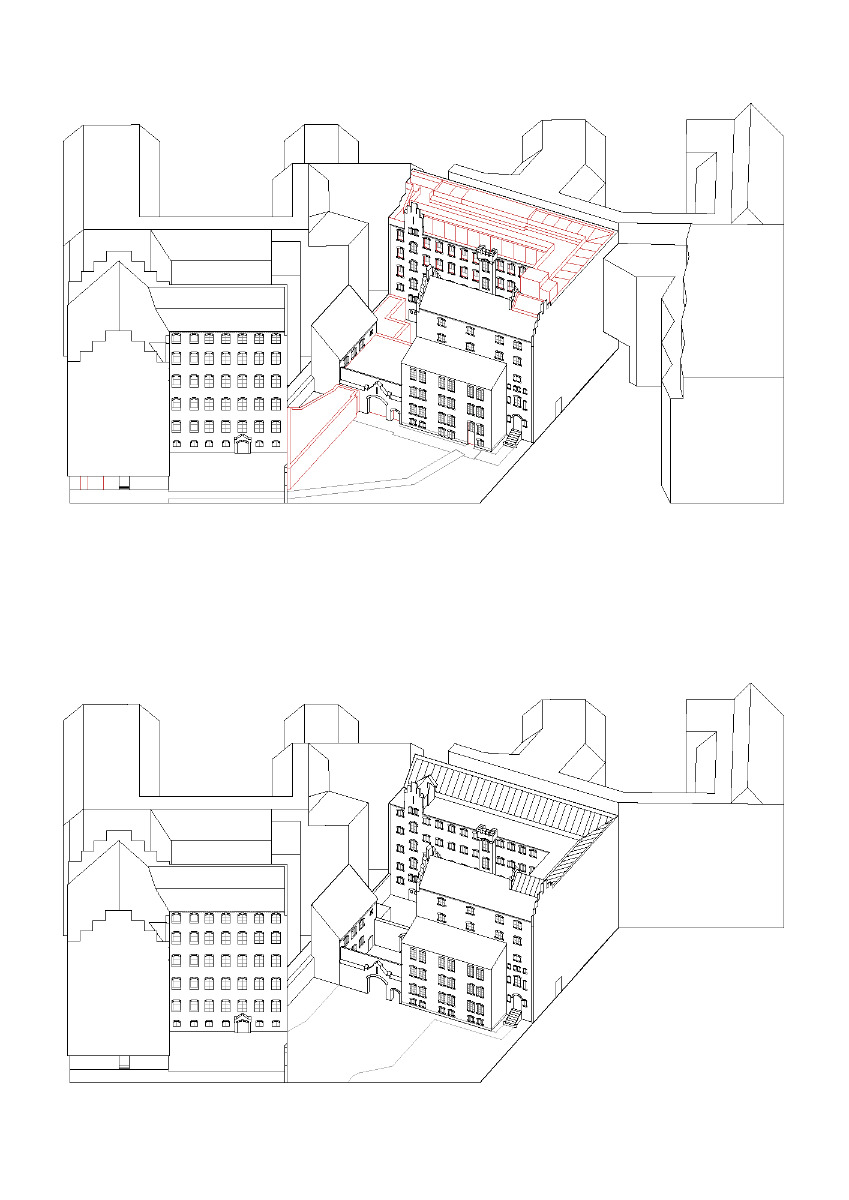

Grüntuch Ernst Architekten have transformed this historically protected brick building, once a women’s prison, into a tranquil oasis. Berliners hardly know the neo-Baroque building, which stands in a normal row of structures on Kantstrasse, a street in the Charlottenburg district. Initially built in 1896 as a criminal court, it looks like an historical townhouse and was last used as an unspectacular land-registry archive. Even less known as it is not visible from the street is the accompanying prison: a many-winged, brick complex in the rear courtyard. During the Nazi period, it served as a prison for women who opposed the regime.

The painstakingly restored brick monument stands hidden among confluent courtyards surrounded by lush greenery. © Patricia Parinejad

An architect’s initiative

Around 2010, an investor approached Berlin’s Grüntuch Ernst Architekten in order to find out what structural potential the historically protected old courthouse and prison had to offer. Used as a women’s prison from the 1930s – when many women from the resistance were incarcerated – until 1986, the place carried a heavy historical burden.

Despite several expert assessments proposing various alternatives for use, the investor lost interest. The architects, however, did not, and in 2012 they acquired the complex to transform the courthouse into a house of culture and art and the prison into a hotel.

© Patricia Parinejad

A sensitive transformation

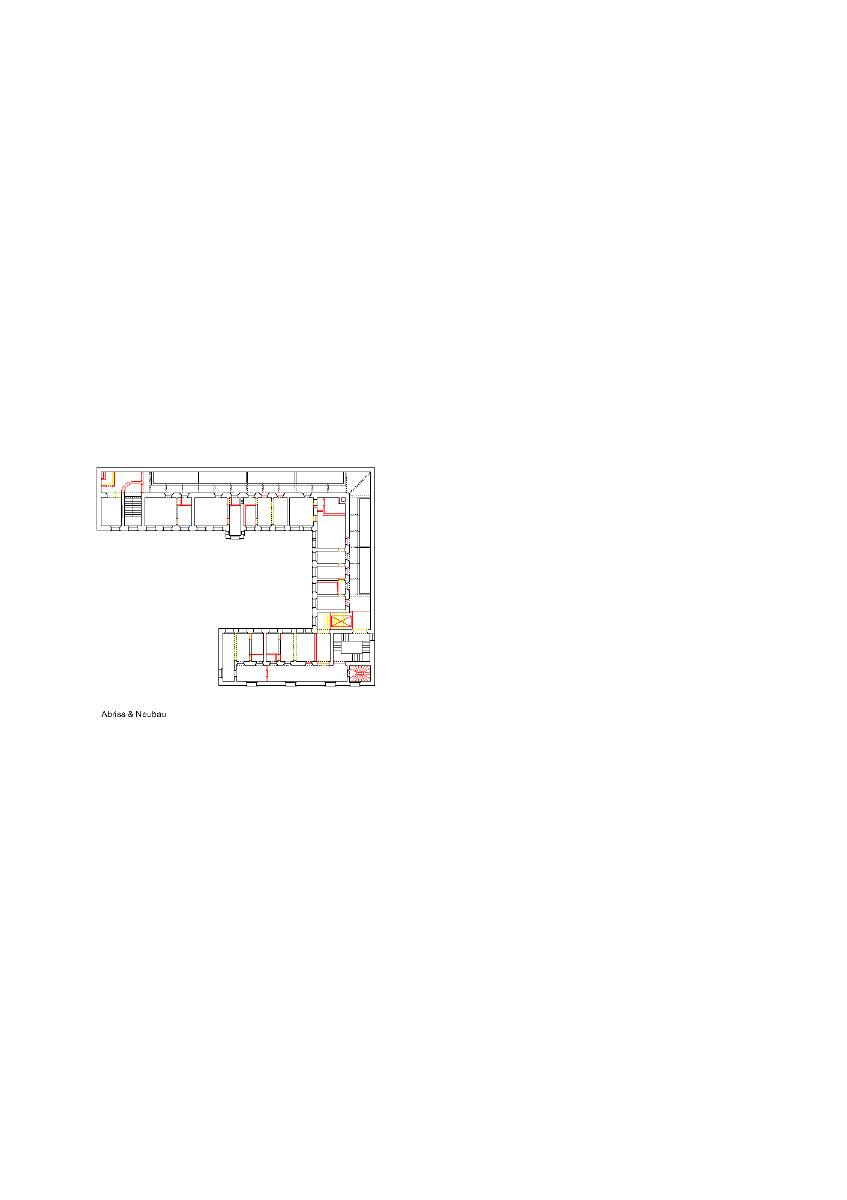

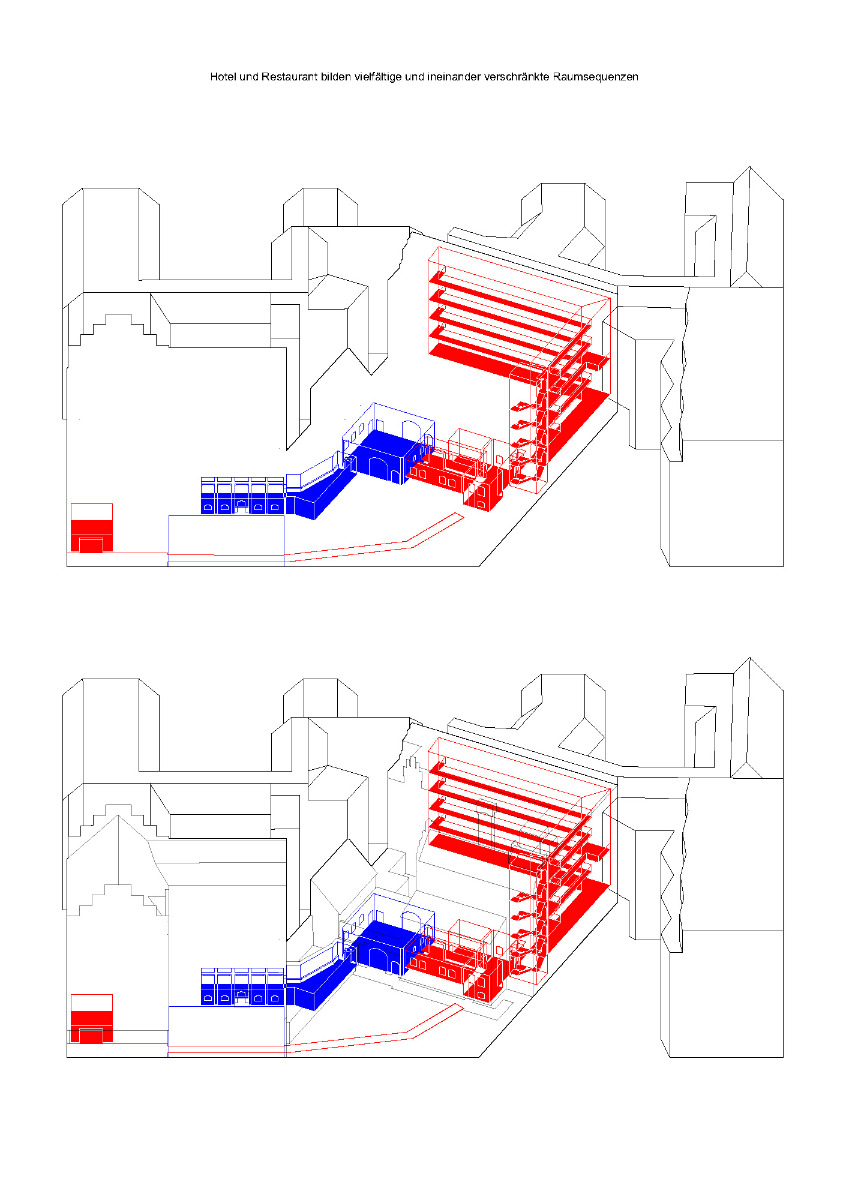

The difficulties inherent in the existing buildings lay in the fact that most of the complex stood in an inner courtyard that was separated from the road, and that the entire spatial program was small-scale and labyrinthine. The plan was to turn a forbidding place into an inviting hotel without shying away from engaging in dialogue with history.

Hanging luminaires by Bocci, which are found throughout the hotel, brighten the space. © Patricia Parinejad

Slumber behind bars

Today, the building is home to 44 guest rooms ranging from small sleeping cabins measuring 11 m² to several penthouse units and a 75-m² suite in the old assembly area.

© Patricia Parinejad

Each room features a unique design; light colours and soft textures characterize the restful ambience. For some rooms, two or three cells were joined by taking out the separating walls. The bars on the high windows have been preserved, though the window openings themselves have been enlarged downwards to allow more daylight and views at eye level. Other rooms have been set in unusually laid-out ancillary spaces and reveal their true personalities only upon entry. One cell has been left in its original state and features a board that provides information about the history of the building, to some extent as a memorial, but also about the National Socialist period.

© Patricia Parinejad

© Patricia Parinejad

Green accents

The old gallery access and atrium have also been preserved. Now freed from its horizontal safety nets, the area is quite bright. The Lovis restaurant on the ground floor has been adapted to the height of the building: the necessary space was found by covering an inner courtyard. The view from the panoramic window in the dining room encompasses a lush, overgrown garden that is strikingly illuminated in the evening.

© Patricia Parinejad

Innovative builders

This is a good example of how even under difficult starting conditions, solutions can be found for building redevelopment projects. It also reflects the tendency for architects to become active in the property business as a way to enable innovative solutions beyond the methods employed by traditional builders’ groups.

Read more in Detail 3.2023 and in our databank Detail Inspiration.

Architecture: Grüntuch Ernst Architekten, Berlin

Client: Wilmina GmbH

Location: Kantstr. 79, 10627 Berlin (DE)

Structural engineering: GTB-Berlin Gesellschaft für Technik am Bau, StudioC Nicole Zahner

Building services: Ingenieurbüro Weltzer

Landscape planning: Marc Pouzol Atelier le balto, Christian Meyer