A translucent patchwork of brick

Holocaust Museum in Melbourne by Kerstin Thompson Architects

The oriel of the old pharmacy is a focal point in the multifaceted brickwork front of the museum. © Derek Swalwell

What architectural expression could possibly do justice to a building that memorializes the horrors of National Socialism? For the Melbourne Holocaust Museum in Elsternwick, a suburb of Melbourne, Kerstin Thompson Architects have taken light as their central design motif: light as a symbol of education and clarification in a new building visited by hundreds of school classes every year.

The patchwork of bricks and glass blocks conceals a variety of wall constructions. © Derek Swalwell

From the outside, this is discernible only at second look, for an historical oriel window and a glazed arched door at one corner are the only larger openings in the streetside facade. The remaining area is covered with a patchwork of grey bricks and glass blocks in various styles of brickwork.

New brickwork surrounds historical stucco gable

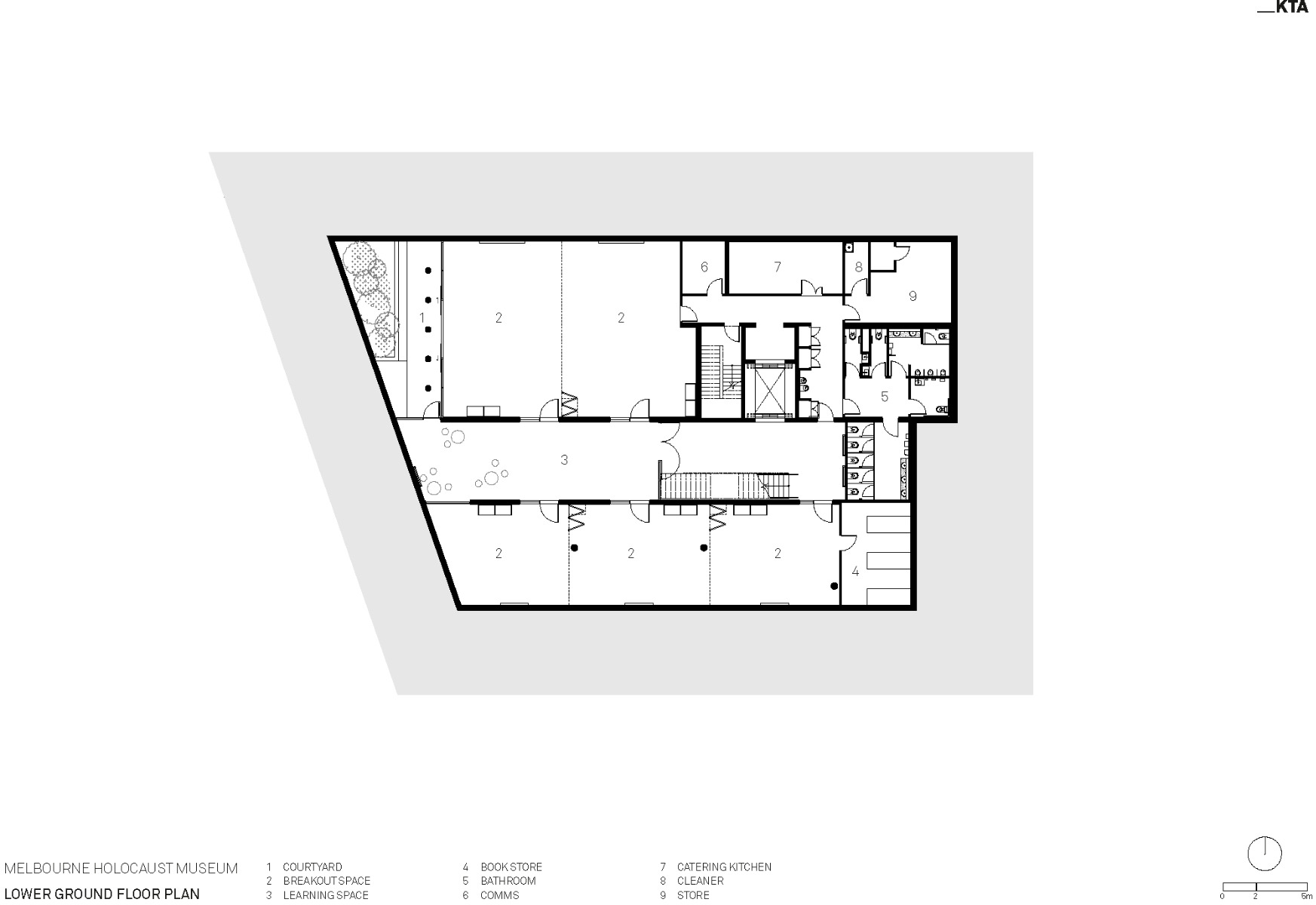

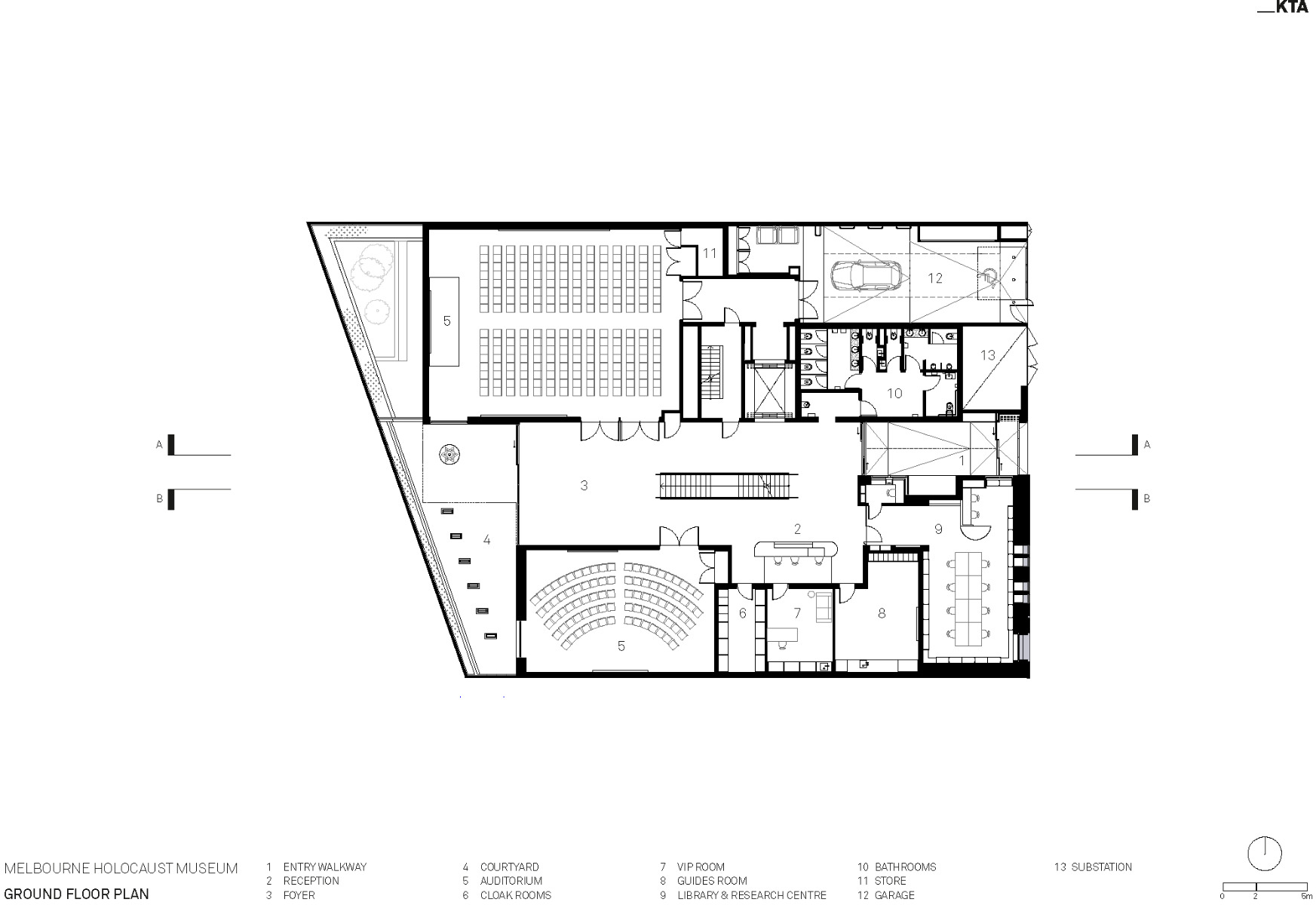

The combination of old and new constructions points to the history of the museum. In 1984, it was established through a private initiative in a former pharmacy from the early 20th century. In 1999, an extension was added next door according to a design prepared by SJB Architects. For the latest restructuring, the client had envisioned a spatial program so ambitious that it would have been unfeasible to realise in either of the two existing buildings. As a result, most building parts were demolished apart from the historical gable end, the striking corner turret and a section of side wall at the southeast corner of the building.

The central access area extends lengthwise through all levels of the building. © Leo Showell

Courtyards and skylights let in the light

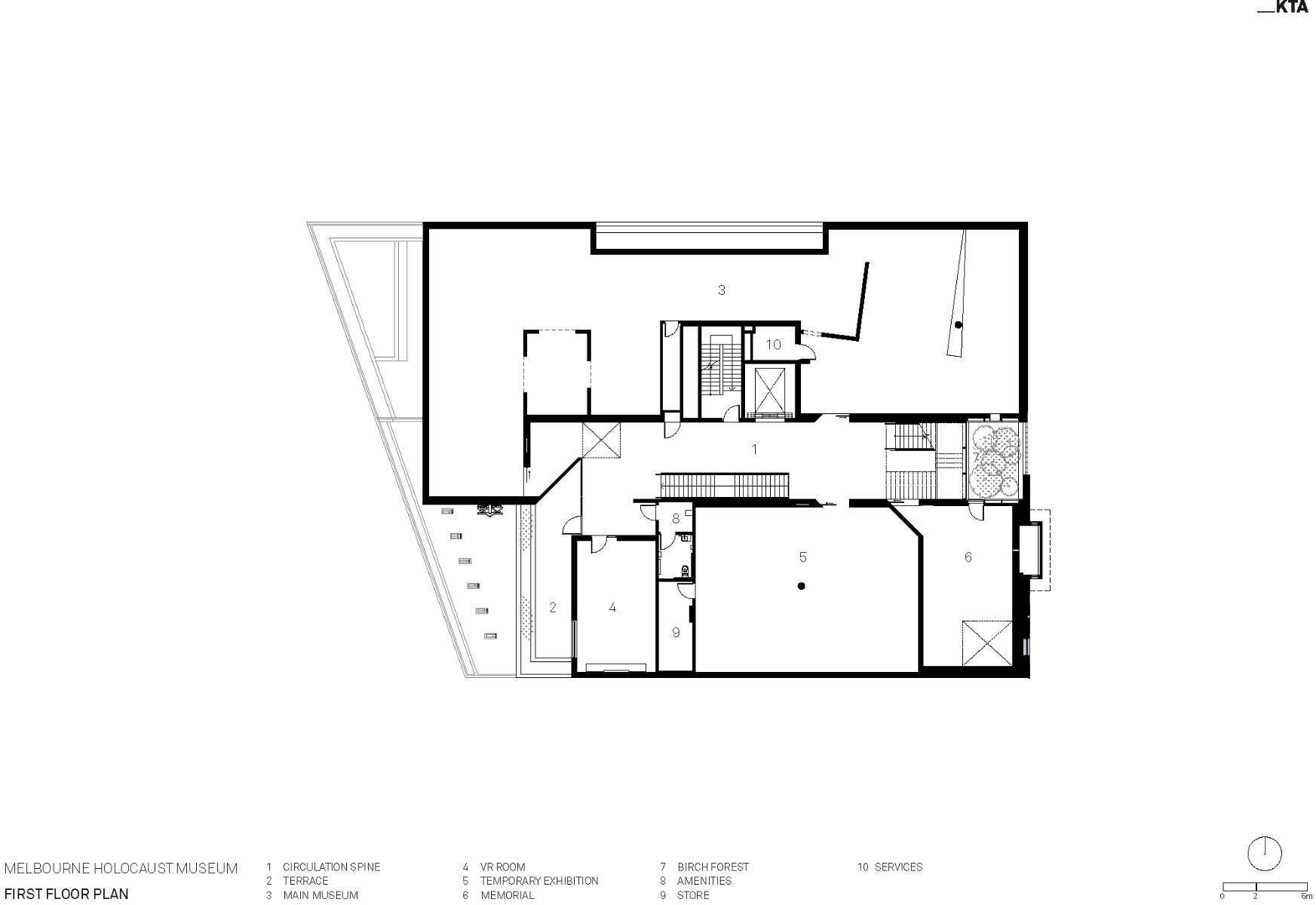

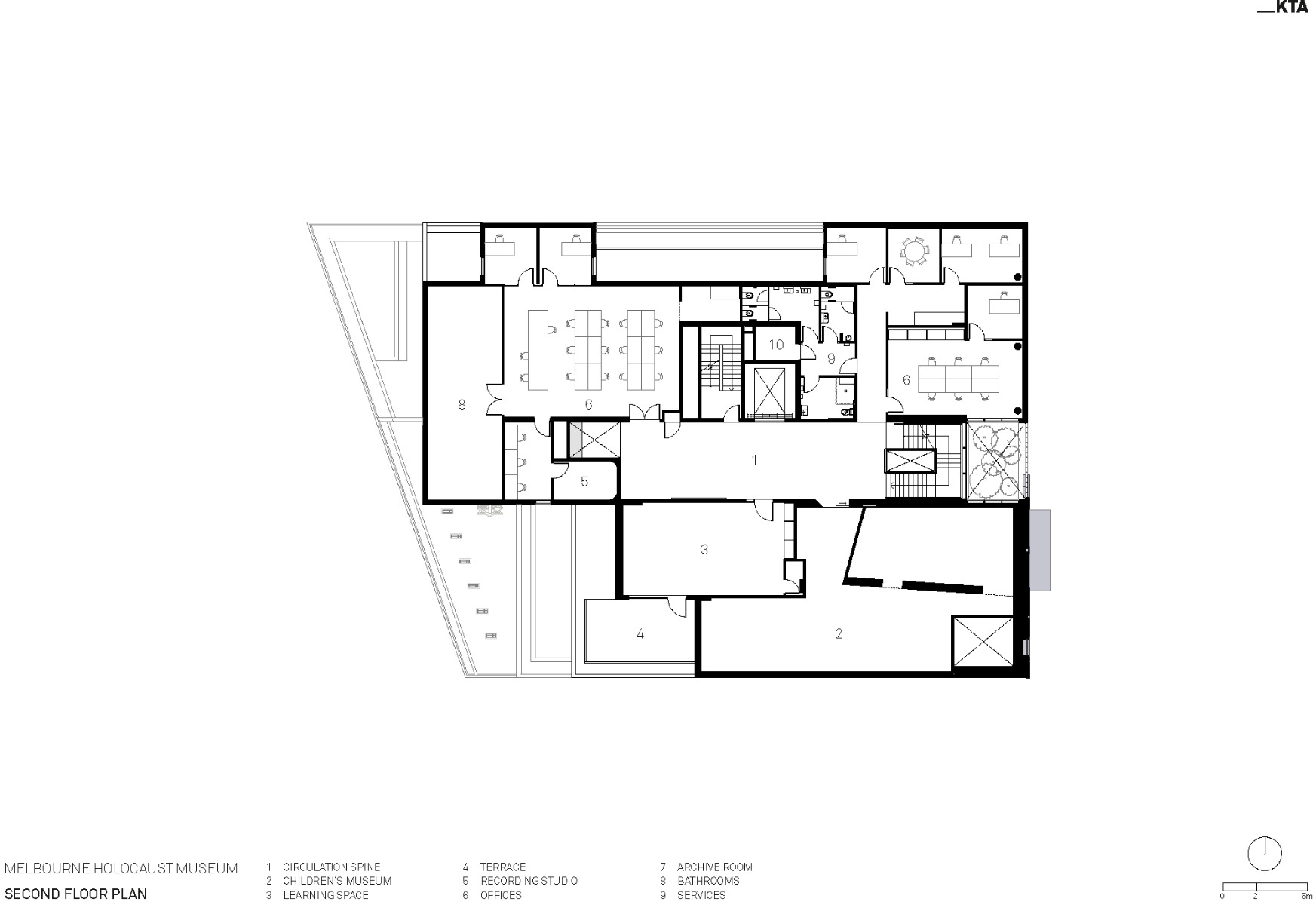

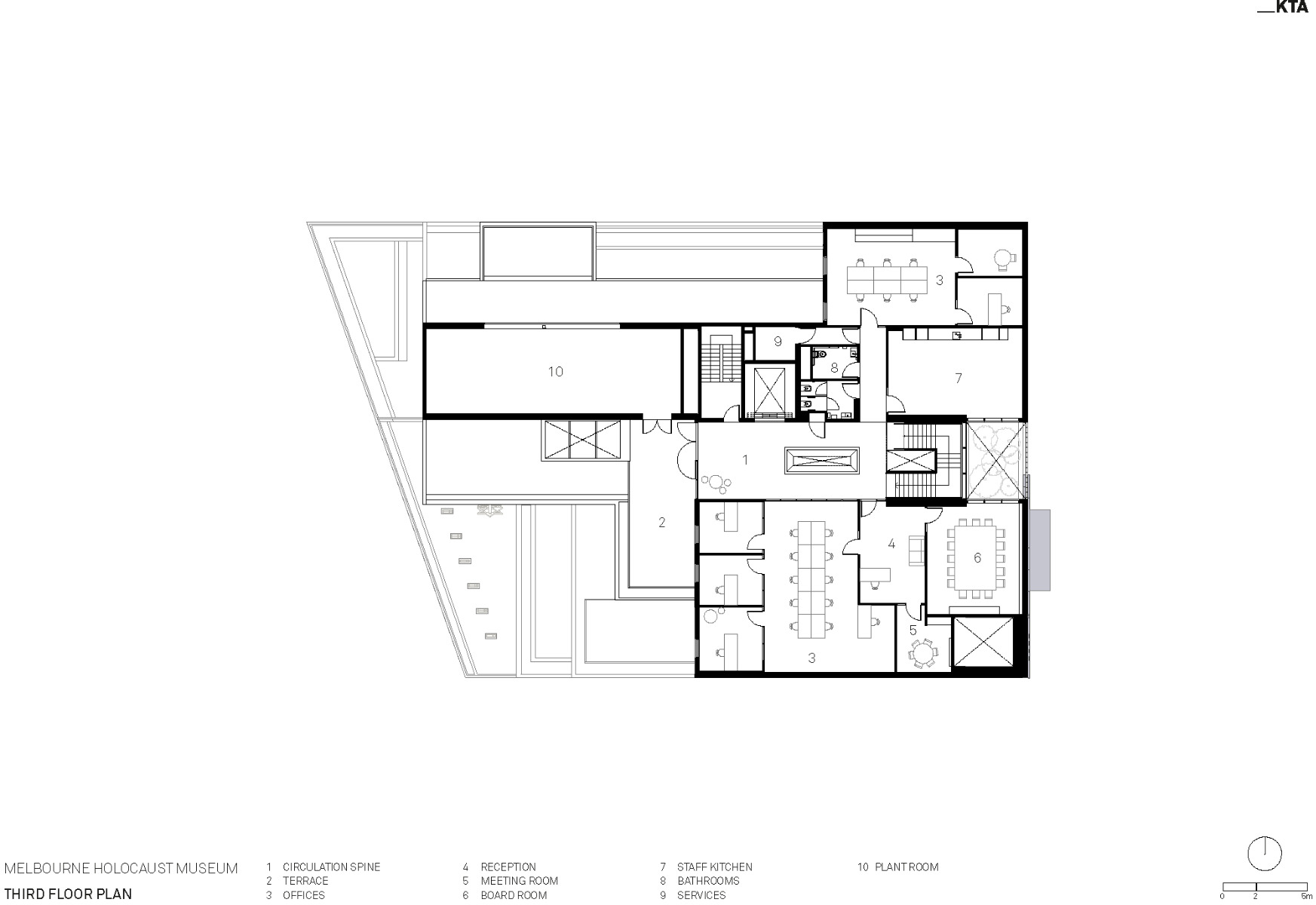

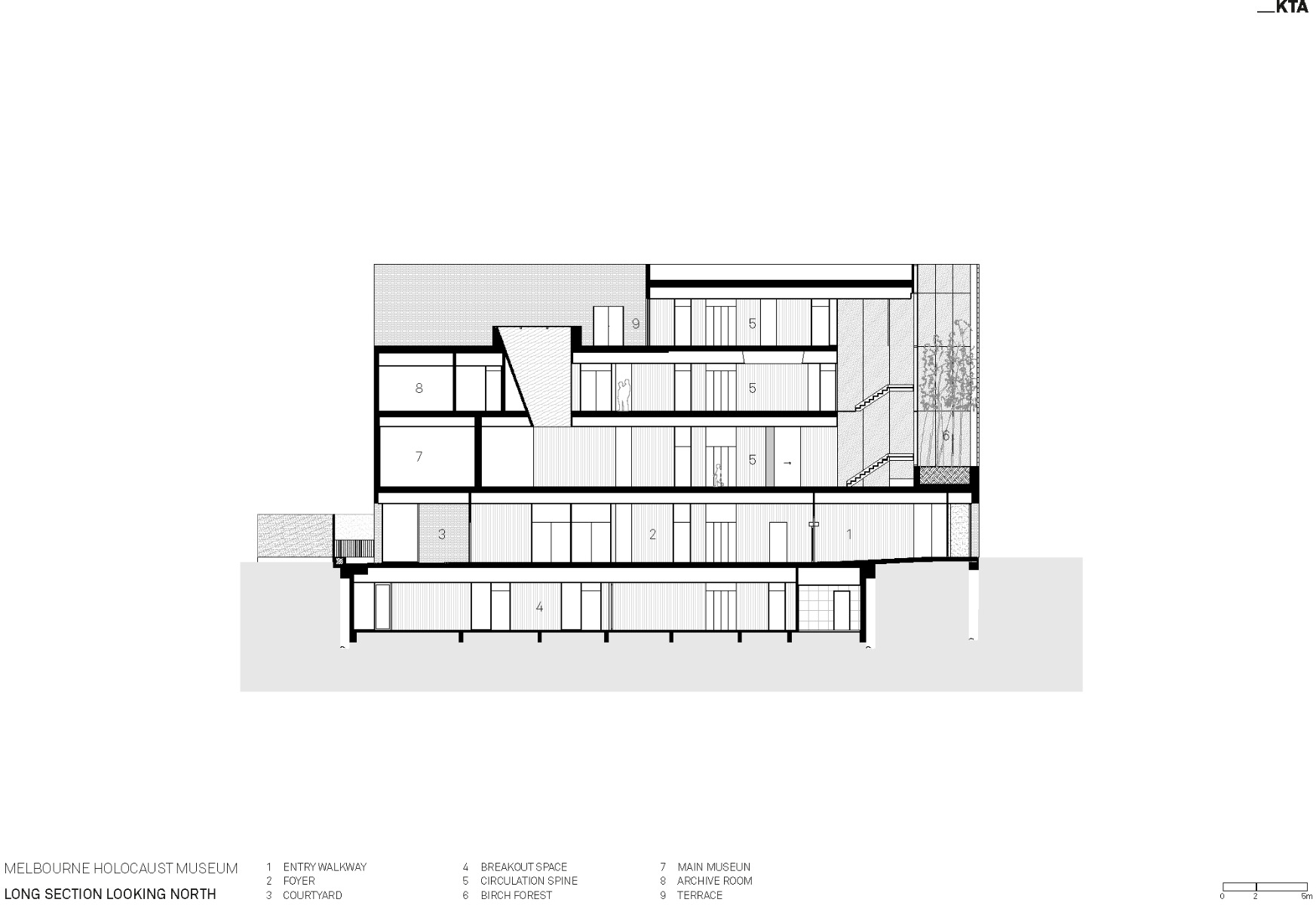

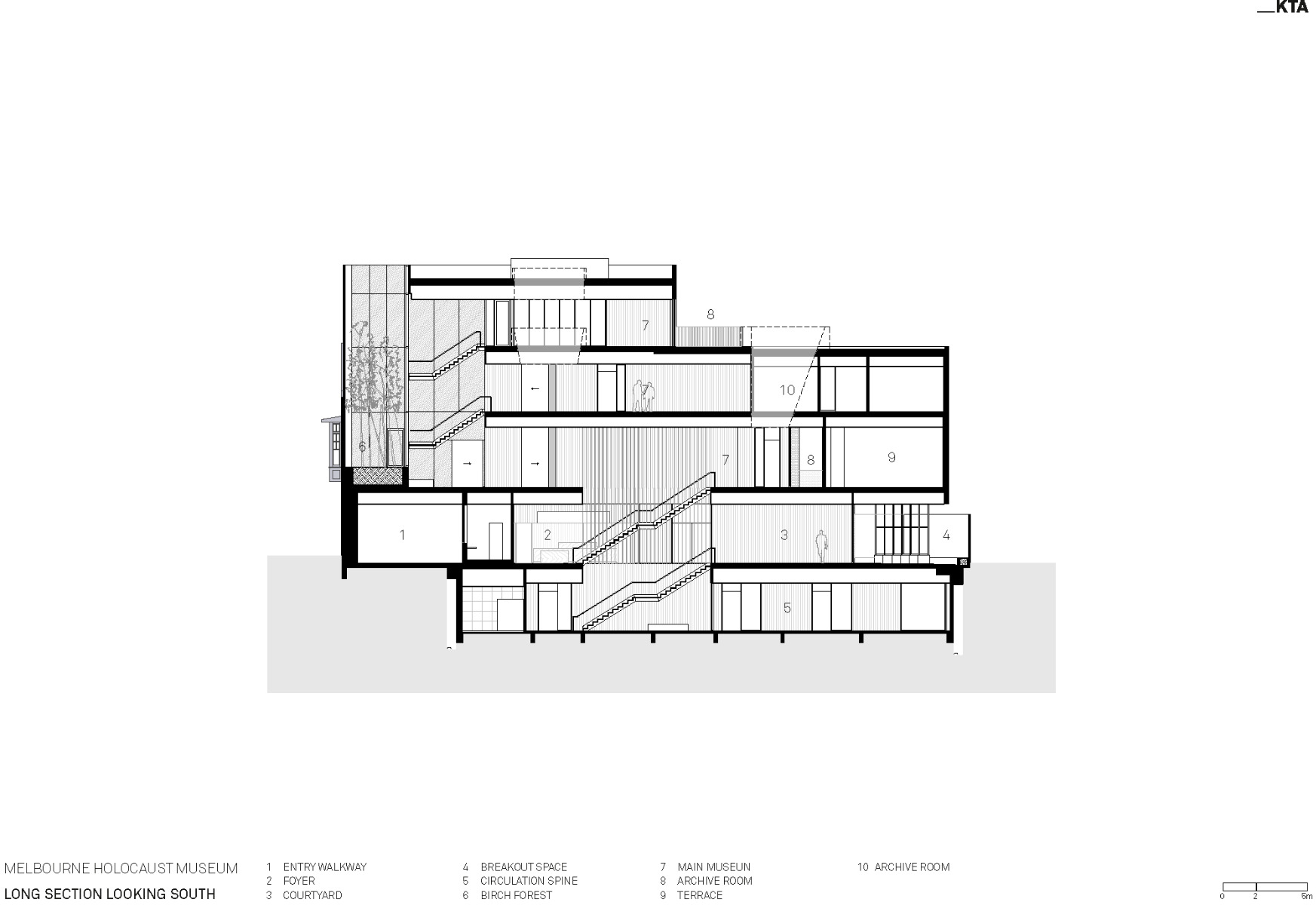

At the centre of the building, a hall-like access zone extends through the entire depth of the structure. There are large terraces on every level, and the ground floor features an inner courtyard with a memorial. The rear side of the building is largely closed off, with light-coloured brickwork and a few room-high windows.

The stairway opens onto a small courtyard that is separated from the road by a translucent brickwork screen. © Derek Swalwell

Towards the road, the access area opens onto an atrium with a stand of birch. An exotic species for Australia, these trees are reminiscent of Europe as the original homeland of Holocaust survivors. The courtyard and road are separated by a light screen of brickwork that becomes lighter as it rises. Bricks and glass blocks alternate on threaded rods of stainless steel. The whole construction is held by a steel skeleton on its back side.

Thanks to the mullion-and-transom facades, even the offices on the upper floor are exposed to natural light from the birch courtyard. © Derek Swalwell

Openness and security in balance

The seemingly homogeneous streetside brickwork conceals many different spaces and wall designs. On the two lower floors, thick walls of prefabricated concrete elements and reinforced shuttering blocks protect the building from potential bombing attacks. Farther up, wherever the spaces need daylight, the facade consists of two layers of bricks and glass blocks. In contrast, in the exhibition areas the architects have combined single-layer brickwork backed by lightweight partition walls.

Read more in Detail 10.2023 and in our databank Detail Inspiration.

Architecture: Kerstin Thompson Architects

Client: Melbourne Holocaust Museum

Location: 13 - 15 Selwyn Street, Elsternwick, Victoria, 3185 (AU)

Structural engineering: Adams Engineer

Facade planning: Inhabit

Landscape architecture: Tract

Building services engineering, acoustics: Cundall

Real estate expert: PLP

Fire prevention: Focussed Fire

Exhibition architecture: Thylacine

Project management: DPPS Projects

Budgeting: Napier Blakely

Contractor: McCorkell Constructions