Where 132 concrete flowers bloom

Digital Structural Engineering for Little Island in New York

© Timothy Schenck

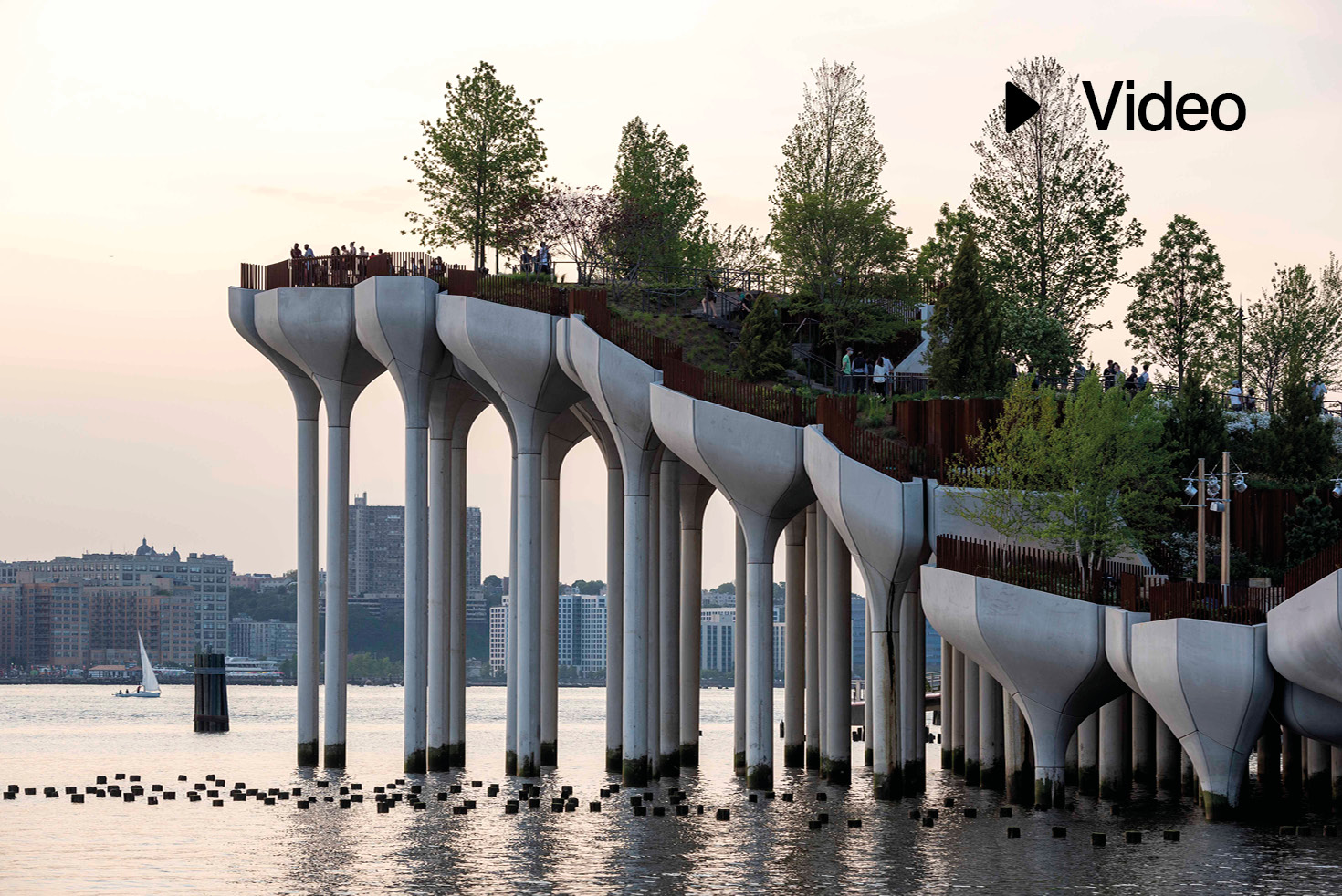

Little Island, a structure measuring 98 x 98 m on each side, is Manhattan’s most extravagant public park. Located in the Hudson River, just off the Meatpacking District on the west side of Manhattan, the approx. $260 million artificial island with sides each in length is the result of financing by the media mogul Barry Diller and planning by Heatherwick Studio supported by Standard Architects, the landscape architecture studio MNLA and the engineers from Arup.

© Timothy Schenck

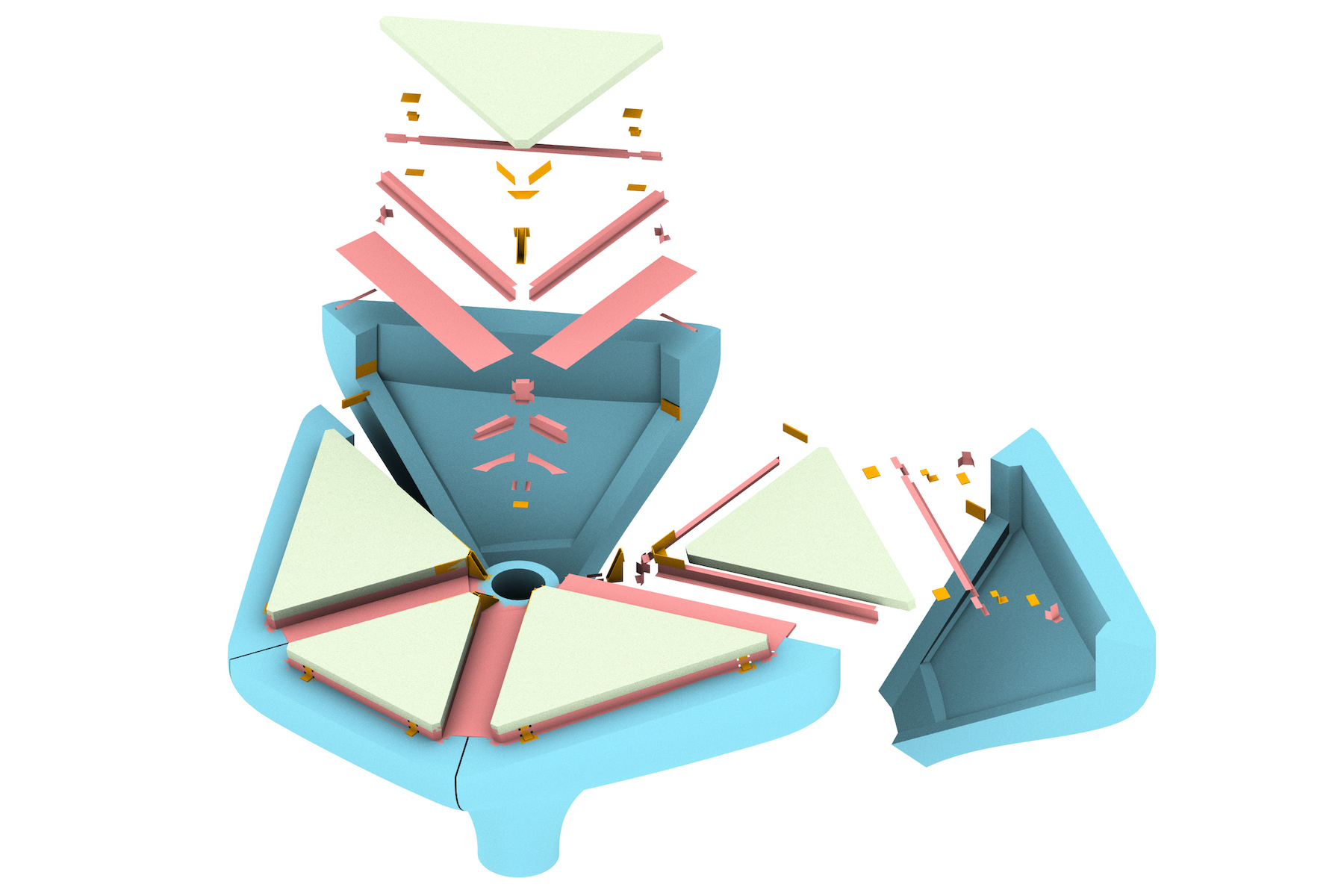

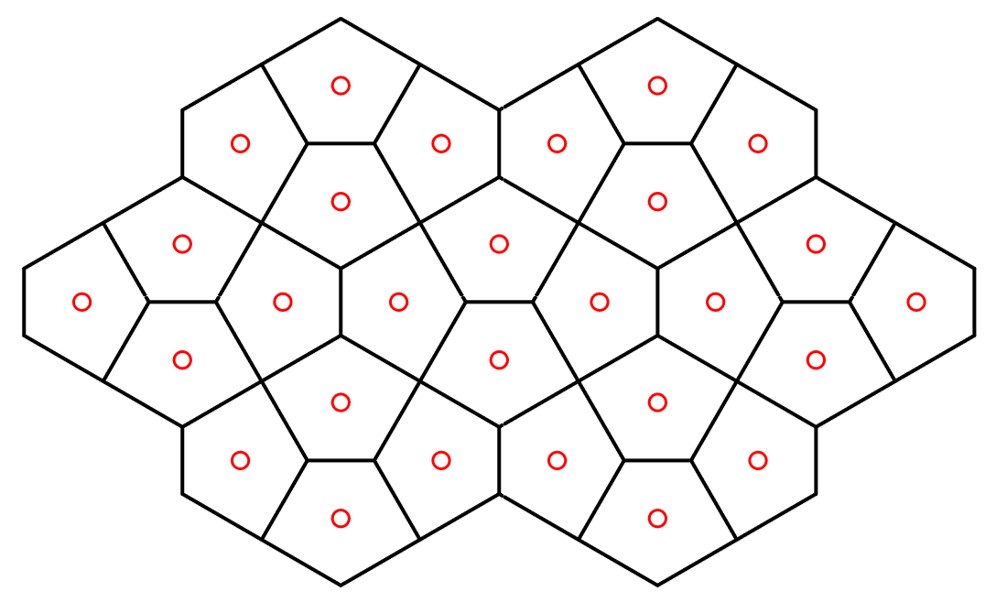

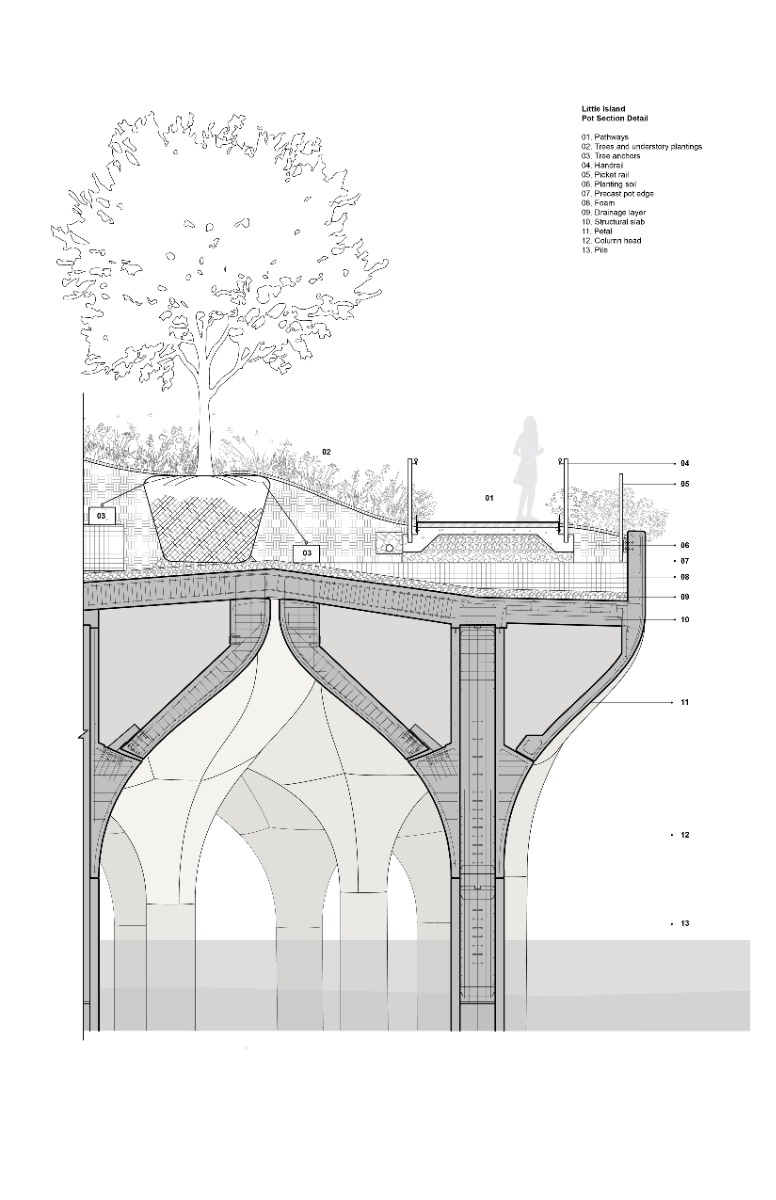

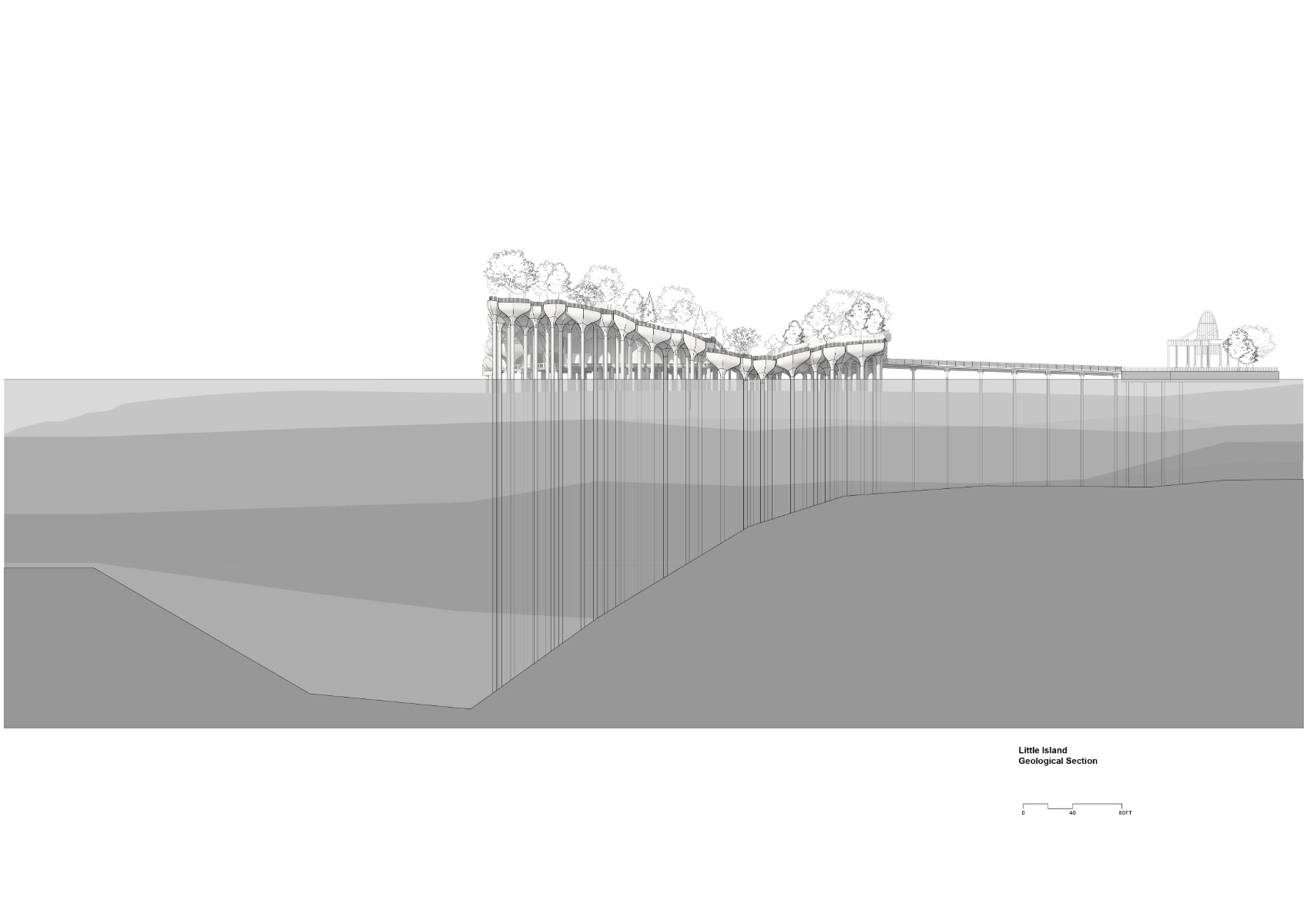

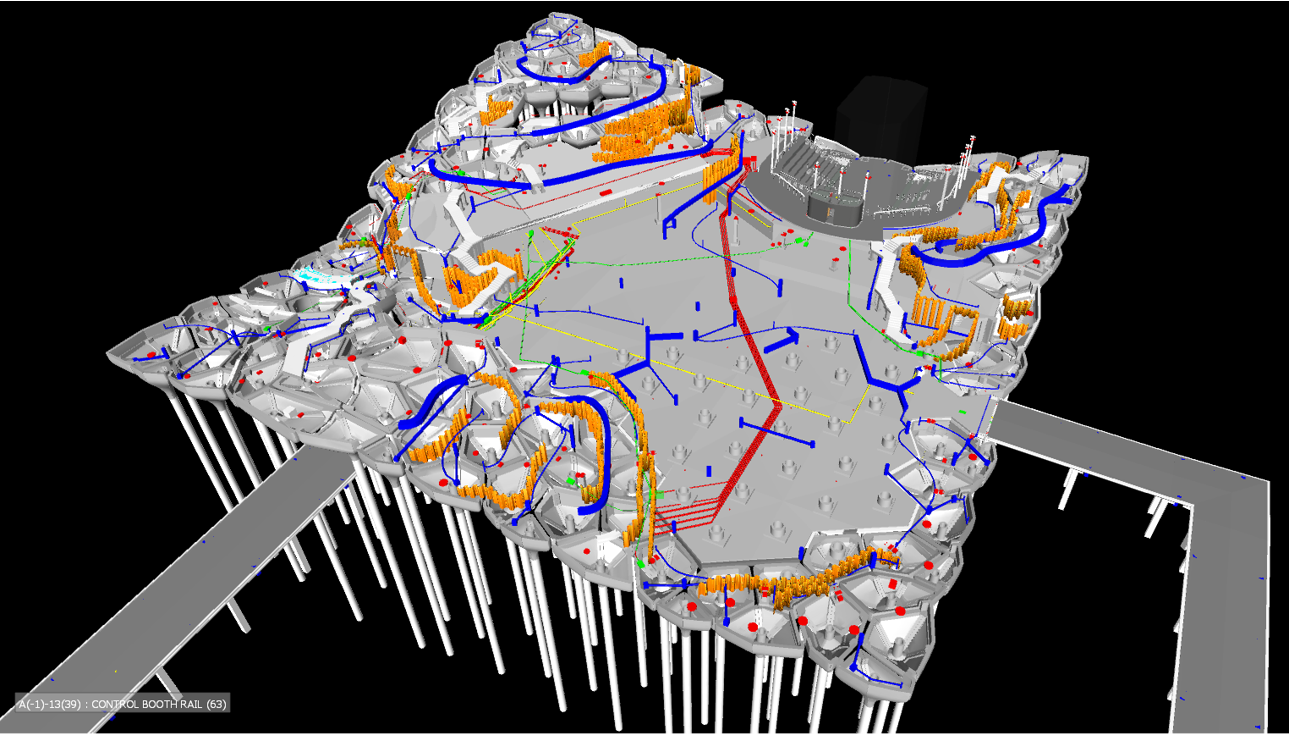

It is seldom – not even for the nearby High Line – for the structural planning of a park to be as important as it was in this case. The park itself lies on 281 prestressed foundation piles, 900 mm thick and driven 73 m down into the riverside silt to reach solid ground. In line with the park’s undulating topography, its upper edges vary between 4.6 and 19 m above the Hudson’s average water level, out of harm’s way from flooding. Prefabricated concrete tulip-shaped pots – 132 altogether – transfer the load of the park into the piles. To rationalise production, the pots have a uniform pentagonal plan geometry with two 90° and three 120° interior angles each, and vary simply in terms of height and their upper edge inclination.

As a result, only twelve different pot shapes were required for fabricating the elements, plus it meant that their concrete formwork could be used multiple times. The pile heads and corners of the concrete pots are joined by star-shaped site-cast concrete beams that in turn support the actual, mainly sloping floor slab of the park. Only the level section in the middle – about 40% of the total area of Little Island – was produced using traditional concrete cross beams and semi-finished slabs.

© Little Island

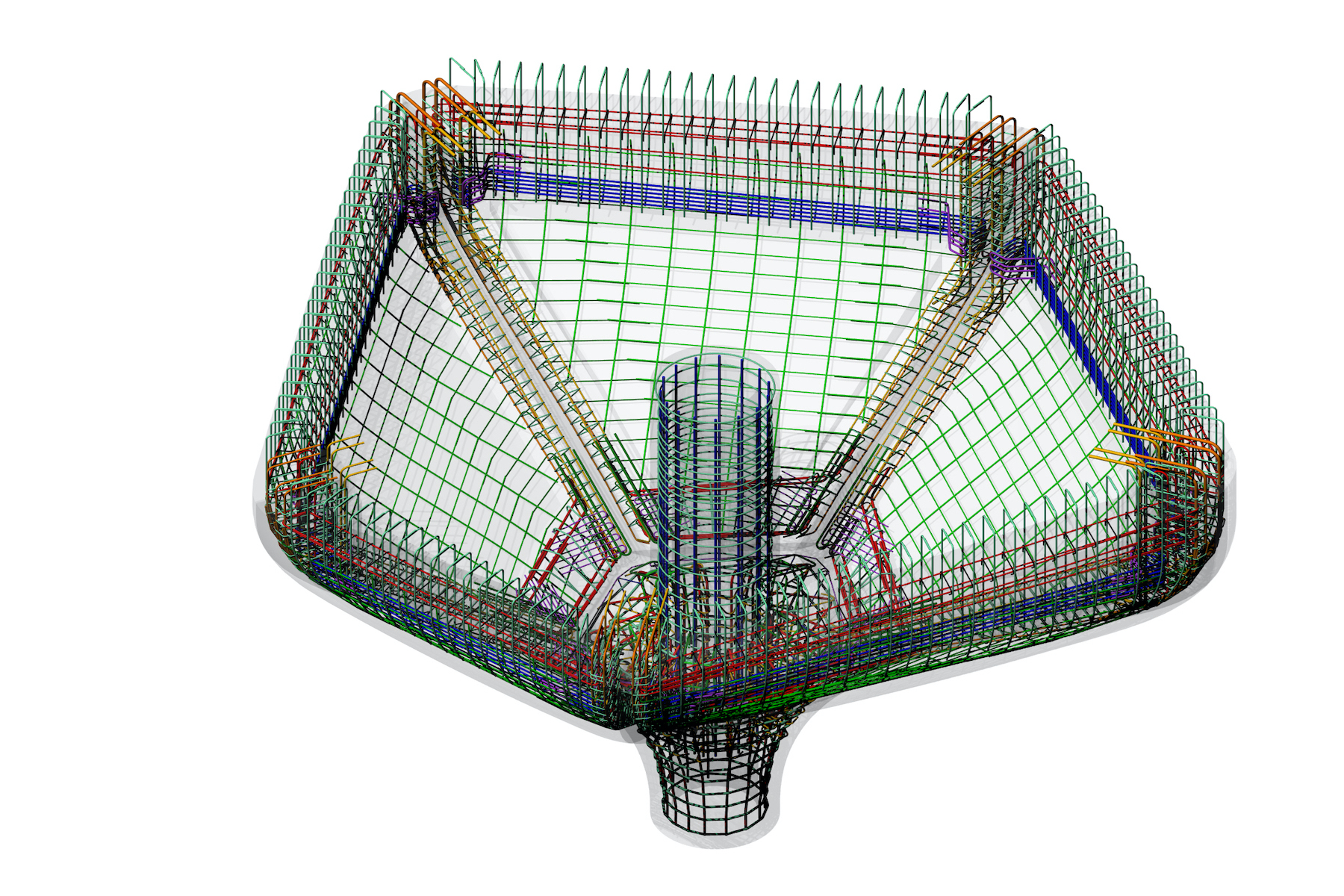

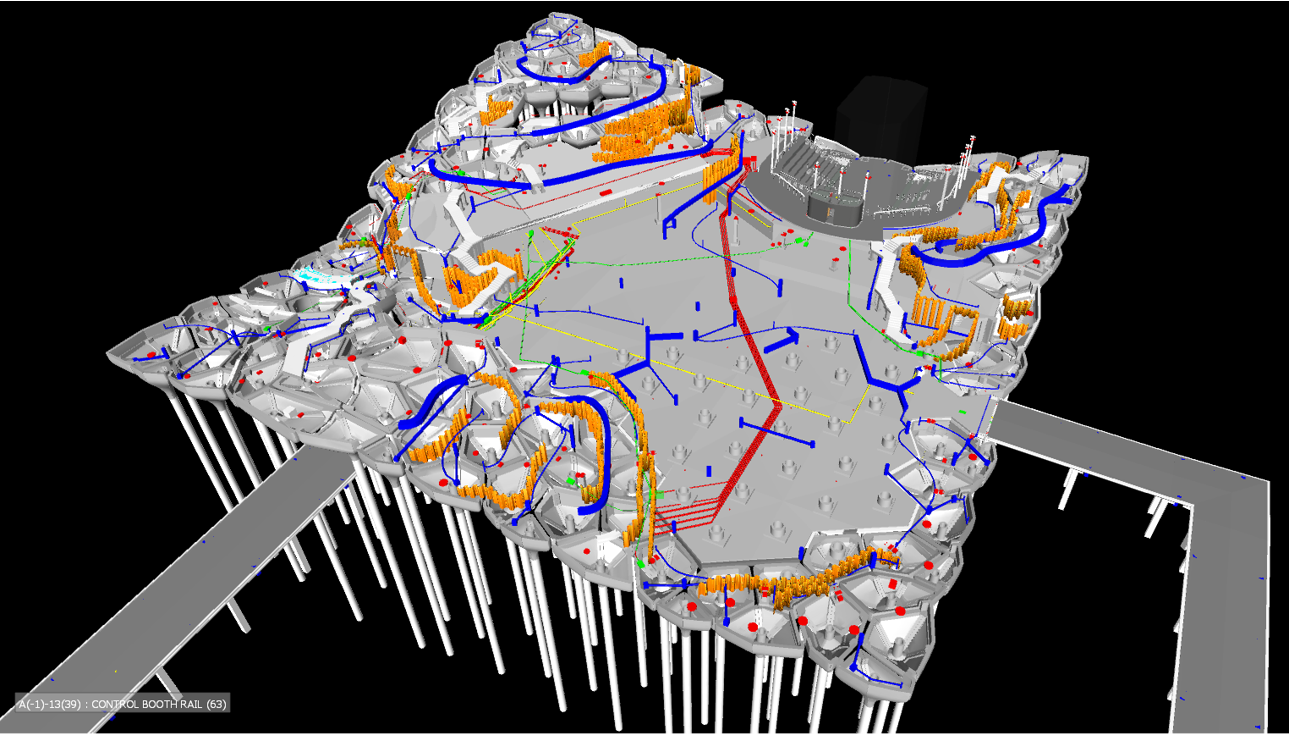

Without continuous 3D planning, it would scarcely have been possible to realize the concrete substructure in this form. All project participants worked with three-dimensional Rhino or other BIM models, while central model coordination was handled using Navisworks by Autodesk. After Heatherwick Studio had defined the outer geometry of the pots, Arup used parametric algorithms to determine the required thickness of the concrete and the siting and geometry of the stainless-steel elements that join the pots together.

© Arup

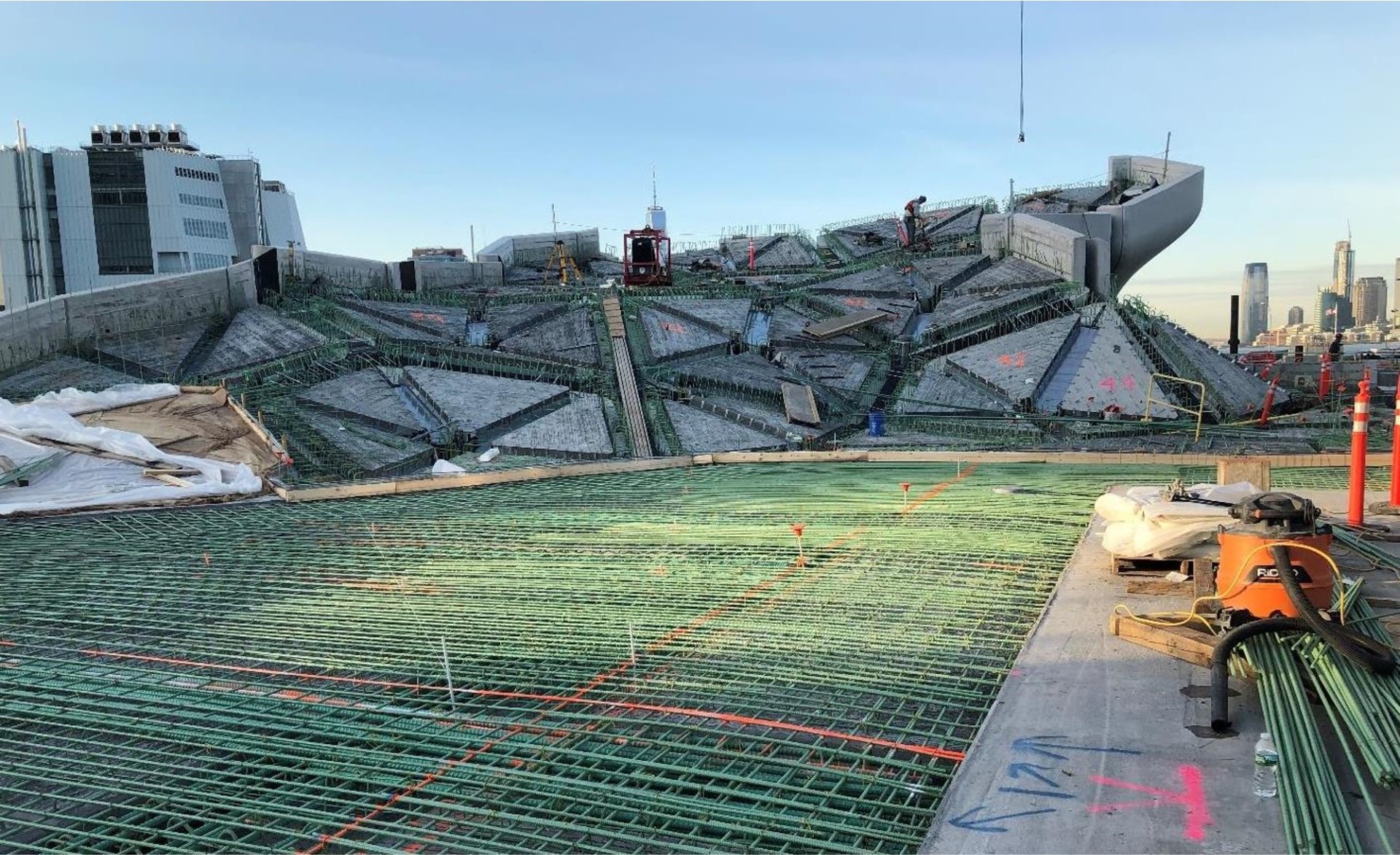

On the basis of the architectural model, the architects derived separate models for the structural calculations and fabrication of the concrete pots. This included all concrete reinforcements, whereby the latter were coated in epoxy resin to protect them from corrosion by the seawater and provided a sizable 75-millimetre concrete overlay. Each individual steel rebar was included in the semantic model, complete with details regarding diameter, siting, bend radius and connections.

© Timothy Schenck

© China News Service, Getty Images

On the basis of these models the precast component fabricators produced the outer formwork of the pots out of milled hard foam blocks, which were then coated in high-pressure sprayed polyurethane to stabilise them for re-use. The inner surfaces, which would not be visible later on, were produced using conventional wood formwork.

© Little Island

The individual petals were then shipped by road from the precast component factory in Saratoga Springs, some 300 km north of New York, to a harbour on the Hudson River. There they were assembled into the tulip-shaped pots before being taken by barge to their destination point in Manhattan.

Architecture: Heatherwick Studio, Standard Architects

Client: Hudson River Park Trust

Location: Pier 55 at Hudson River Park, Hudson River Greenway, New York (US)

Landscape architecture: MNLA

Structural engineering, Building services engineering, Fire protection: Arup