98.5 % Ecology: Bloomberg Office Building in London

Foto: Nigel Young

Michael Bloomberg is a media entrepreneur, billionaire, former mayor of New York City – and a UN special envoy for cities and climate change. At the climate summit held in Bonn in the autumn of 2017, he was among those well-known Americans who stood in stark opposition to their own president in advocating more climate protection throughout the world.

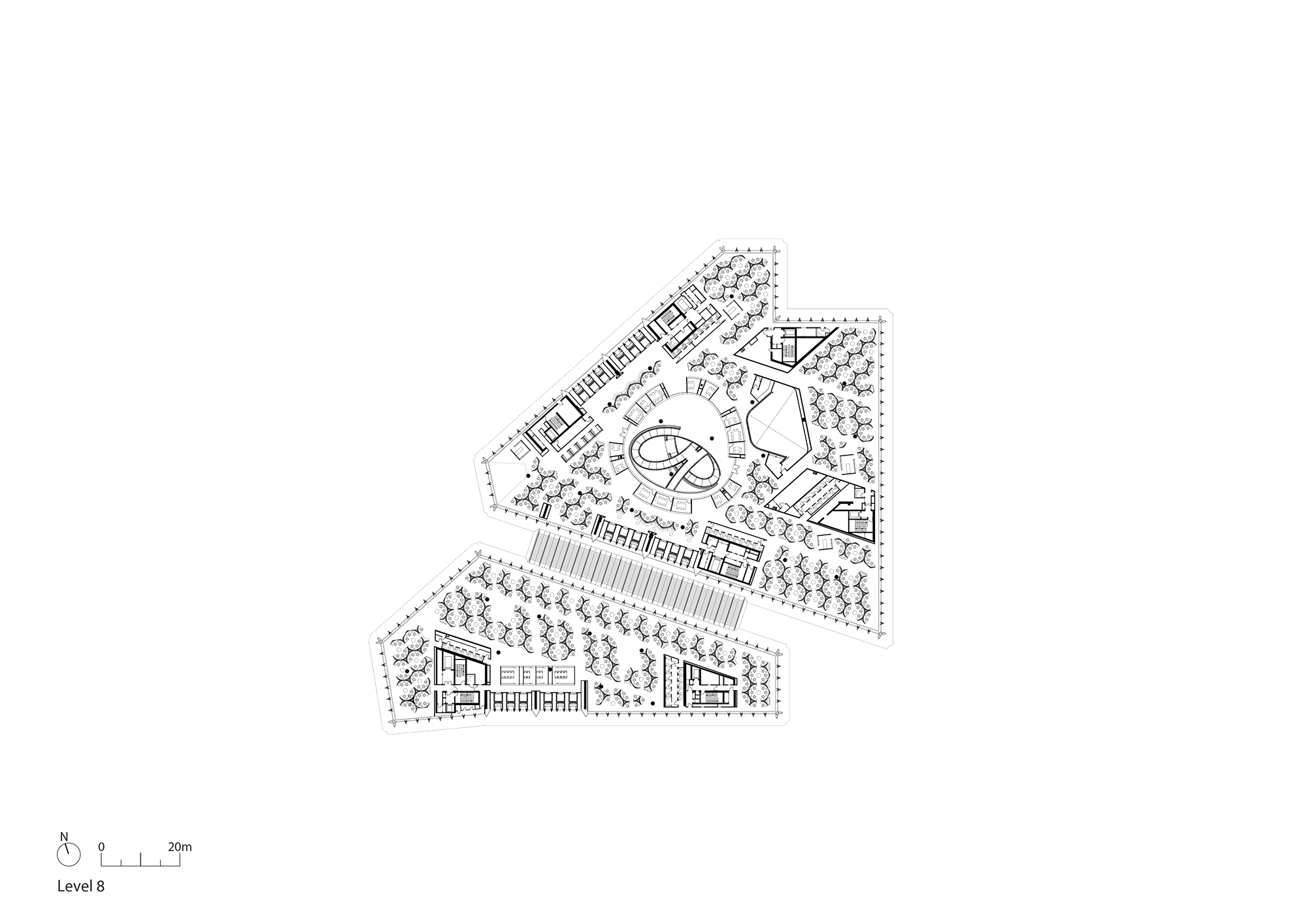

Anyone who stands for such a worthy cause must also live by his words in his working life. Therefore, for the new European headquarters of his media concern in London Bloomberg strove for high ecological standards. On the other hand, the new complex is refreshingly reticent when it comes to the current rivalry for the City’s tallest building. Its façades of glass, sandstone and bronze sheeting rise just eight storeys and are topped off with two recessed attics. Altogether, around 4,000 employees work in the open-plan offices.

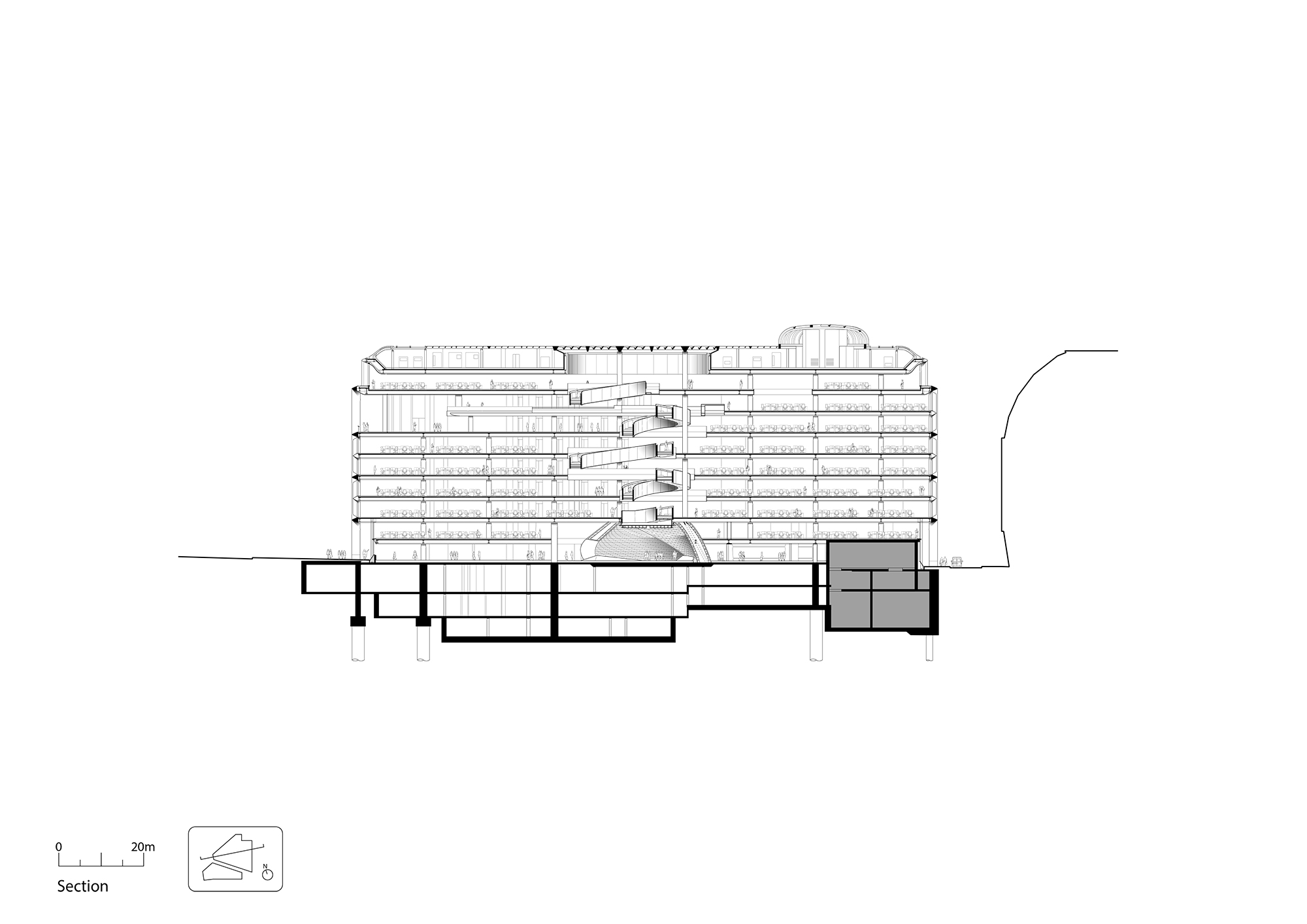

Bloomberg’s new HQ stands just a stone’s throw away from the Bank of England in the City of London. Across the way, James Stirling’s postmodernist One Poultry, a commercial structure known both for its appealing ugliness and its current status as England’s youngest listed building. At the three corners of the lot, Foster + Partners created small public squares. Moreover, a public (if somewhat narrow and gloomy) shopping passage divides the massive building volume into two parts. According to Bloomberg, they continue the course of a roadway that has existed there since ancient times. Another relic can be seen in the basement of the new structure: the part-reconstruction of a late-Roman temple of Mithras which once stood on virtually the same spot.

With 98.5 % of all the possible points, the Bloomberg building achieves the highest ranking ever awarded to a larger office building within the framework of a design-stage assessment in the UK’s BREEAM sustainability system. This is obvious in terms of the building’s water consumption (73 % lower than a standard building of the same size) and CO₂ emissions (35 % lower than legally allowed for office buildings in the UK). According to the architects, the CO₂ economy corresponds to 600 tonnes every year – as much as a car would emit in 120 circumnavigations of the earth.

Even the façades show that energy efficiency plays a great role here. Broadly protruding, voluminous sunshades made of bronze cast shade; their integrated, soundproof flaps serve the natural ventilation. Because this alone is not enough to provide natural air intake, the building has a ventilation system that directs fresh air primarily to areas where sensors show a particularly high CO₂ content in the interior air (and thus more employees). Every storey has about 70 of these sensors: one for every eleven work stations.

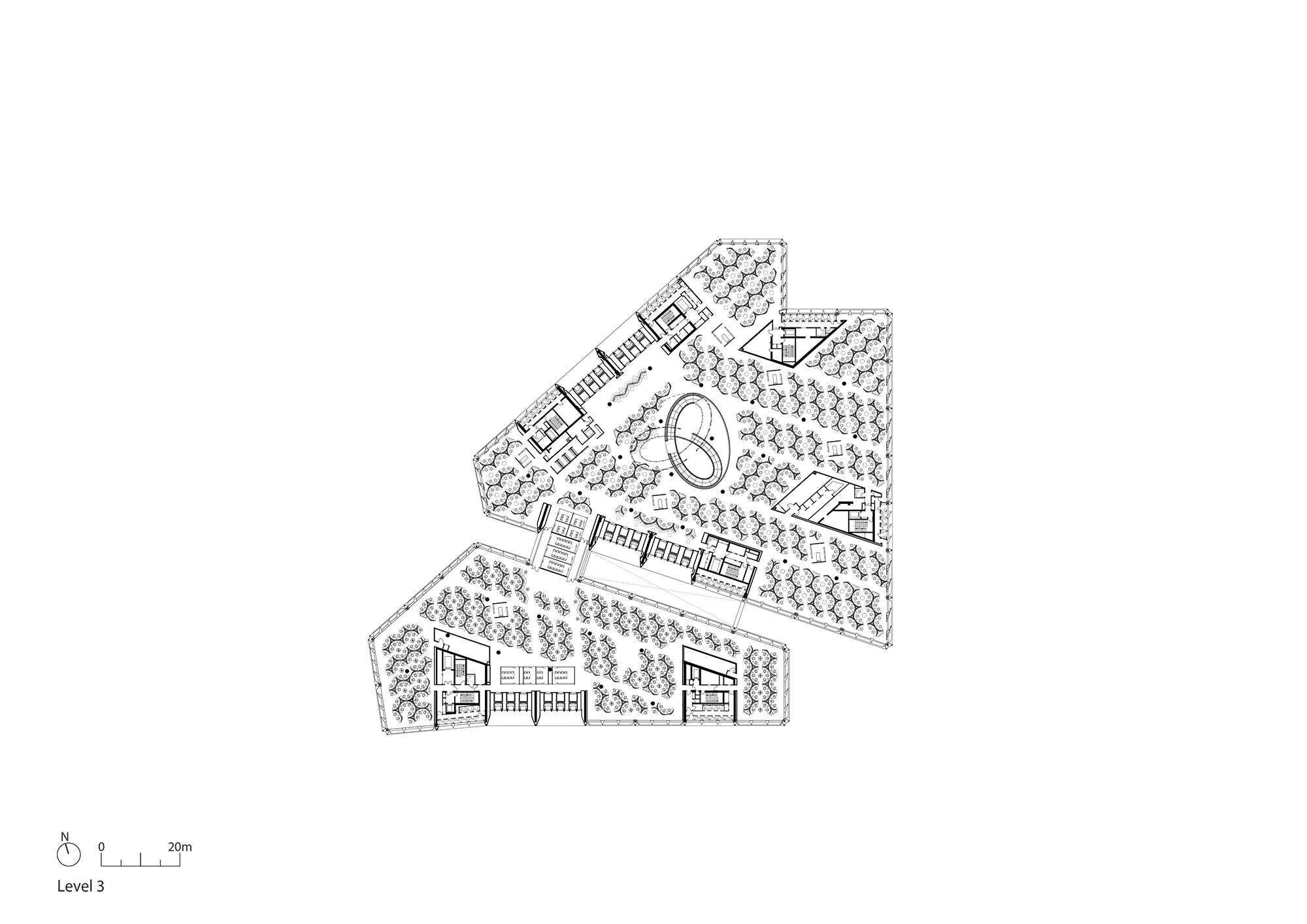

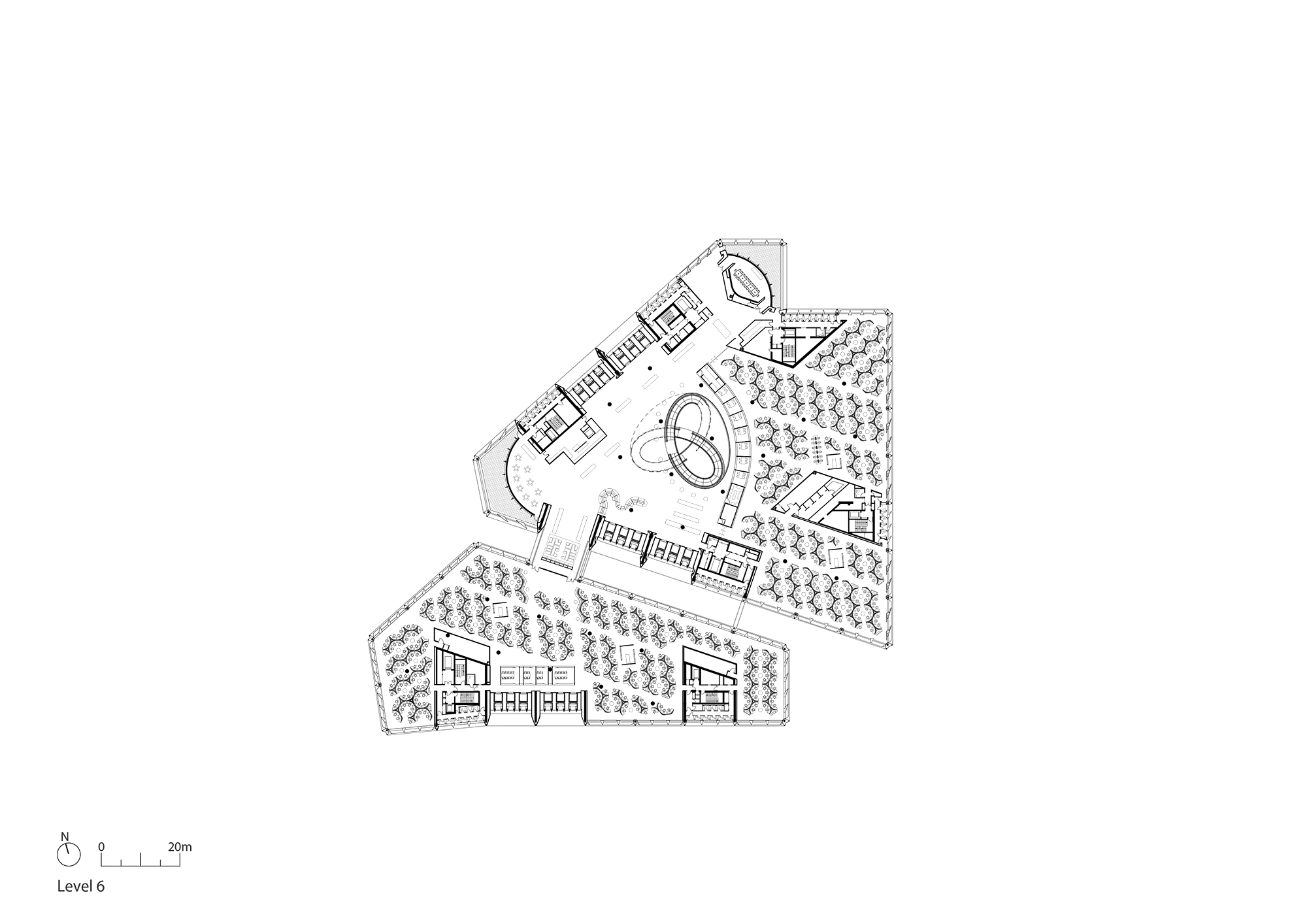

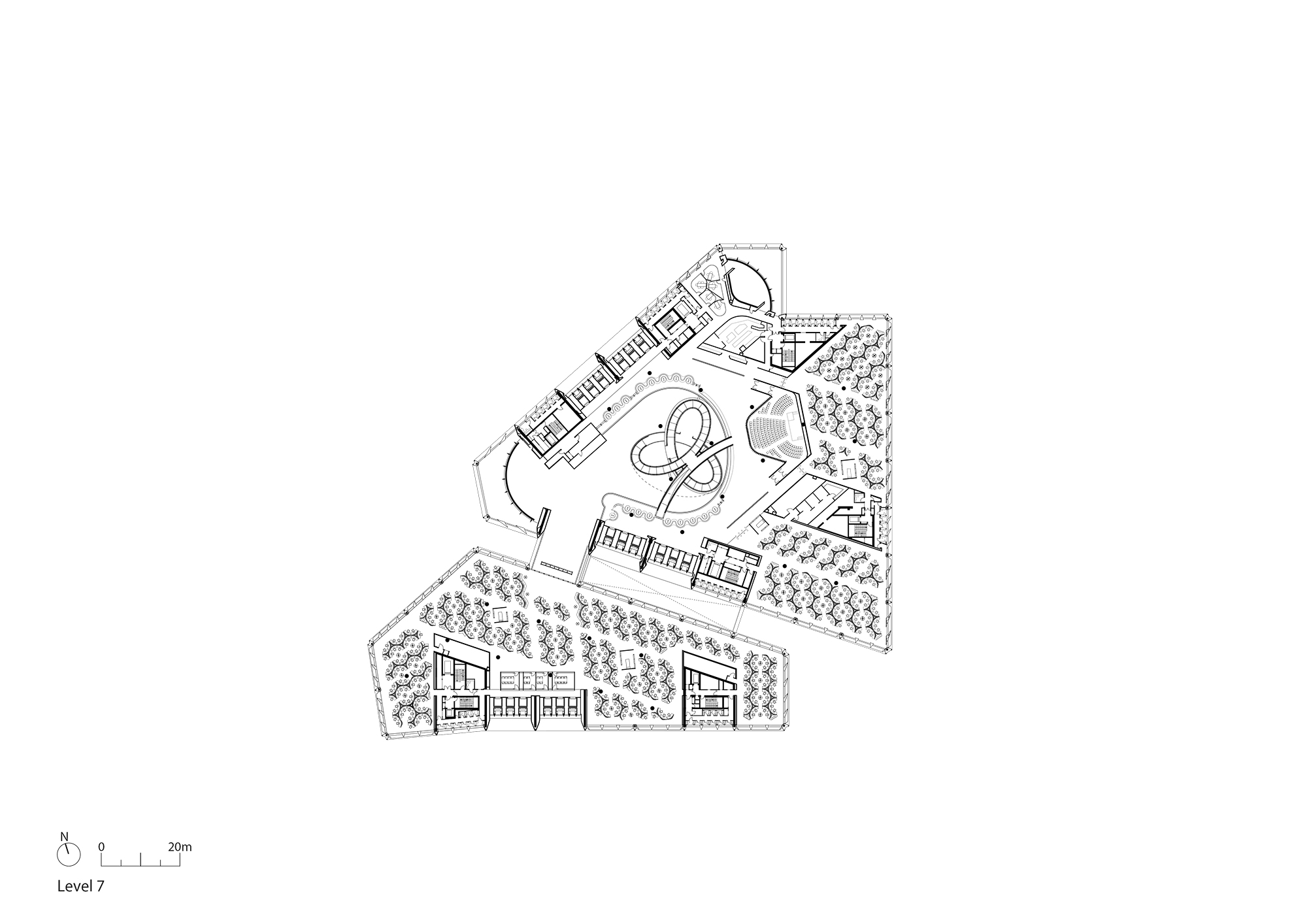

Open-plan offices dominated the upper levels. In order to allow at least a bit of light into the deep ground plan, the architects have added a glass-covered atrium to the larger of the two structures. Here, a 200-metre cloverleaf access ramp runs through all the office levels. The traditional vertical access with lifts and stairwells has been banished to the corners of the building.

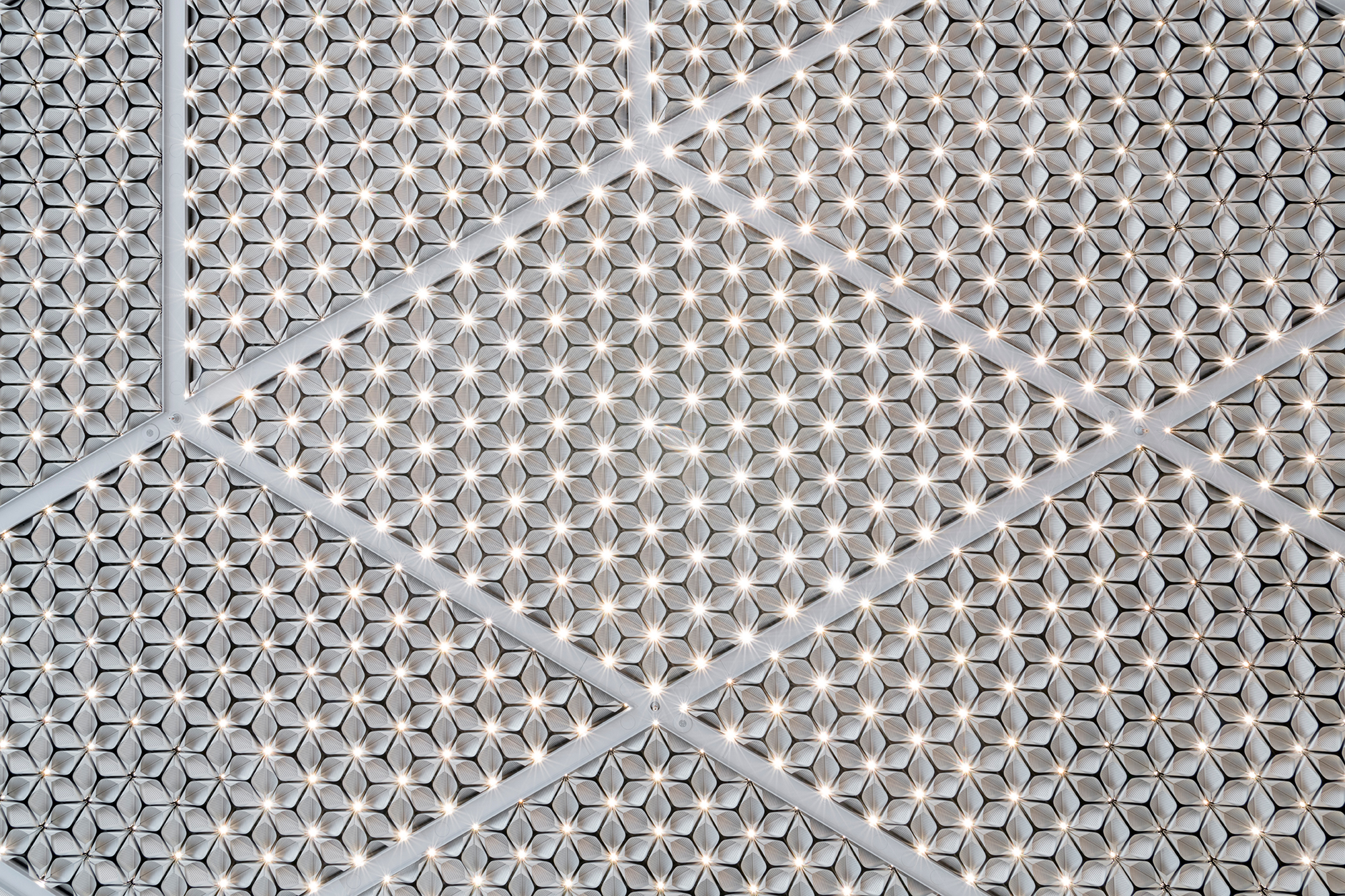

The office ceiling, which has a touch of the Oriental, is another eye-catcher that reveals itself as a true multitasker. Cooling, lighting and soundproofing are integrated in the 4,000-odd ceiling panels. The 500,000 LEDs will conserve around 40 % of the energy used by conventional lighting tubes. The faceted underside of the metal ceiling also increases the area for cold radiation. Furthermore, metal is a good heat conductor, meaning that the cooling ceiling can be operated with higher flow temperatures than other, comparable systems.

The complex draws electricity and heat from a gas-driven cogeneration unit on the grounds. Thanks to an absorption chiller, the heat generated there can also be used to cool the building. A rooftop photovoltaic system helps keep Bloomberg’s power bills down.

Water recycling is yet another important component of the sustainability strategy. Rainwater from the roof, the water from the recooling works of the chilling system and from the sinks and showers is collected and used in flushing the toilets. In order to reduce the need for water there, vacuum toilets have been installed in the entire building. These use only one-seventh as much water as ordinary toilets.

With energy-efficient building uses such as these, grey energy usually plays a supporting role. But the architects have made an effort here as well: the structural work for the building used concrete whose aggregate contains up to 60 % recycled materials.

Anyone who stands for such a worthy cause must also live by his words in his working life. Therefore, for the new European headquarters of his media concern in London Bloomberg strove for high ecological standards. On the other hand, the new complex is refreshingly reticent when it comes to the current rivalry for the City’s tallest building. Its façades of glass, sandstone and bronze sheeting rise just eight storeys and are topped off with two recessed attics. Altogether, around 4,000 employees work in the open-plan offices.

Bloomberg’s new HQ stands just a stone’s throw away from the Bank of England in the City of London. Across the way, James Stirling’s postmodernist One Poultry, a commercial structure known both for its appealing ugliness and its current status as England’s youngest listed building. At the three corners of the lot, Foster + Partners created small public squares. Moreover, a public (if somewhat narrow and gloomy) shopping passage divides the massive building volume into two parts. According to Bloomberg, they continue the course of a roadway that has existed there since ancient times. Another relic can be seen in the basement of the new structure: the part-reconstruction of a late-Roman temple of Mithras which once stood on virtually the same spot.

With 98.5 % of all the possible points, the Bloomberg building achieves the highest ranking ever awarded to a larger office building within the framework of a design-stage assessment in the UK’s BREEAM sustainability system. This is obvious in terms of the building’s water consumption (73 % lower than a standard building of the same size) and CO₂ emissions (35 % lower than legally allowed for office buildings in the UK). According to the architects, the CO₂ economy corresponds to 600 tonnes every year – as much as a car would emit in 120 circumnavigations of the earth.

Even the façades show that energy efficiency plays a great role here. Broadly protruding, voluminous sunshades made of bronze cast shade; their integrated, soundproof flaps serve the natural ventilation. Because this alone is not enough to provide natural air intake, the building has a ventilation system that directs fresh air primarily to areas where sensors show a particularly high CO₂ content in the interior air (and thus more employees). Every storey has about 70 of these sensors: one for every eleven work stations.

Open-plan offices dominated the upper levels. In order to allow at least a bit of light into the deep ground plan, the architects have added a glass-covered atrium to the larger of the two structures. Here, a 200-metre cloverleaf access ramp runs through all the office levels. The traditional vertical access with lifts and stairwells has been banished to the corners of the building.

The office ceiling, which has a touch of the Oriental, is another eye-catcher that reveals itself as a true multitasker. Cooling, lighting and soundproofing are integrated in the 4,000-odd ceiling panels. The 500,000 LEDs will conserve around 40 % of the energy used by conventional lighting tubes. The faceted underside of the metal ceiling also increases the area for cold radiation. Furthermore, metal is a good heat conductor, meaning that the cooling ceiling can be operated with higher flow temperatures than other, comparable systems.

The complex draws electricity and heat from a gas-driven cogeneration unit on the grounds. Thanks to an absorption chiller, the heat generated there can also be used to cool the building. A rooftop photovoltaic system helps keep Bloomberg’s power bills down.

Water recycling is yet another important component of the sustainability strategy. Rainwater from the roof, the water from the recooling works of the chilling system and from the sinks and showers is collected and used in flushing the toilets. In order to reduce the need for water there, vacuum toilets have been installed in the entire building. These use only one-seventh as much water as ordinary toilets.

With energy-efficient building uses such as these, grey energy usually plays a supporting role. But the architects have made an effort here as well: the structural work for the building used concrete whose aggregate contains up to 60 % recycled materials.